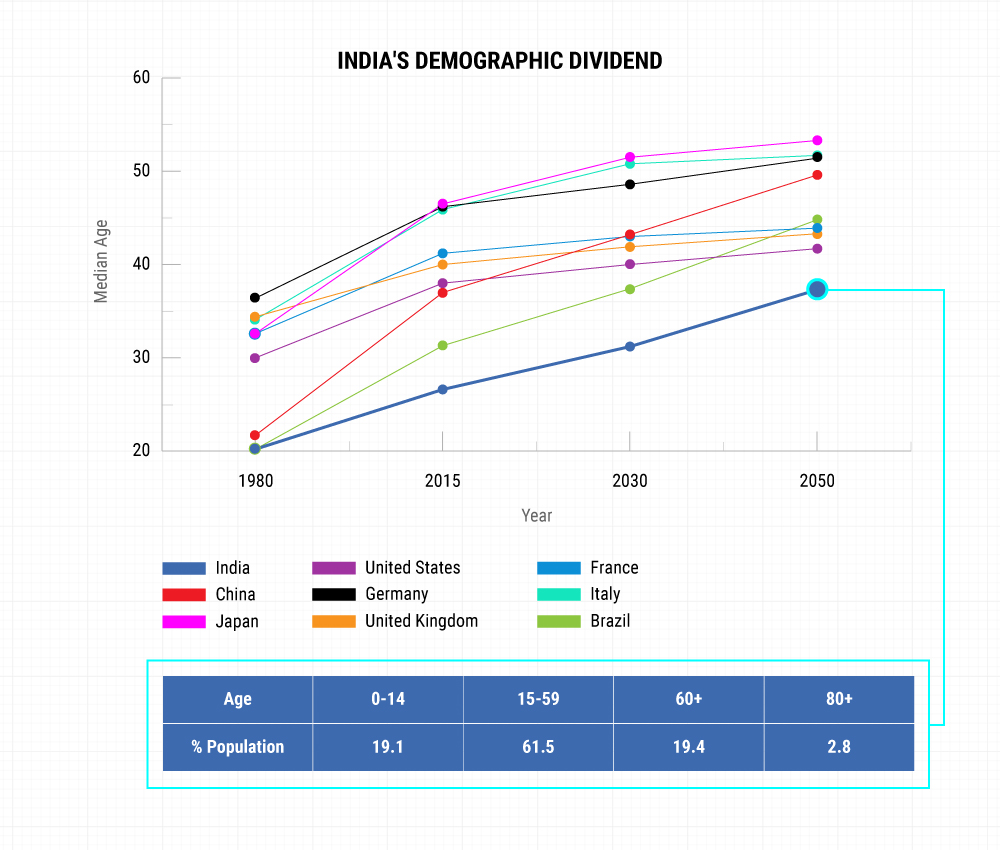

India’s demographic dividend puts it in a unique place in the world economy. Even as the world ages, India is beginning to flex the muscles of its predominantly young, productive age group — 62.6% of its population falls in the 15-59 age bracket, according to this Census report.

Is this a boon or a curse? On the face of it, it’s a wonderful thing. Demographic dividend is a proven booster to growth, resulting in speedier rise of wealth and resulting consumption — both indicators of economic progress.

Scratch a little deeper and you’ll realise that this demographic dividend may not translate into any real benefits for India. Simply because there aren’t enough jobs to accommodate its huge youth bulge. Without jobs, the demographic dividend can’t contribute to the GDP.

India is adding fewer and fewer jobs each year across sectors even a million Indians become age-eligible for jobs every month. A study by Delhi-based civil society organisation PRAHAR claimed that employment could shrink by seven million by 2050.

And this is happening against a background of great disruption that technology, especially automation and artificial intelligence, is wreaking across sectors, industries and job markets.

What’s the future of economic growth and jobs in India? Is the China model — large-scale manufacturing powering the rise of the middle class — the right one to follow? Will our demographic dividend turn into a curse or do we still have hope it will reap benefits?

In a ground-setting interview with FactorDaily, Nandan Nilekani, the early architect of the India Stack, shares his perspective on the future of jobs and how it could affect millions of Indians.

Q. What is your view of the future of jobs in India?

A. I think creating ample jobs that are fulfilling and provide good income to people is the single biggest challenge facing India today. Thanks to our demographic dividend, we have the youngest population in the world and we’re going to have that for a long time to come. Creating millions of jobs every month, every year, is at the heart of economic growth and social stability. People’s aspirations have gotten unleashed, thanks to the media and the internet (greater exposure and awareness). These have to be met.

The challenge we have is unique. When countries like Japan, South Korea, China and others in Southeast Asia started on the path to development, they could take up manufacturing at scale; so, they became manufacturing powerhouses and they participated in globalisation. Initially, they began by manufacturing shoes and clothes, but eventually moved to high-end electronics; today, they’ve become manufacturing world-beaters. This was the model that powered their growth.

India’s job creation has to be domestic-led and services-led. The Indian model will be agriculture to services as opposed to agriculture to manufacturing to services

Unfortunately, for us at this point, this model may not be viable for various reasons. The first is a politico-cultural reason. Globalisation itself is under threat and there is a movement towards closed, nationalistic economies as evidenced by Brexit, the rise of Donald Trump, etc. The second is technology disruption where we are seeing the rise of automation in manufacturing through robotics, 3D printing, artificial intelligence (AI) and the Internet of Things (IoT). Because of this, manufacturing is achieving higher productivity and lower costs with fewer employees. The third reason is the legacy of our global growth over the last few decades resulting in Chinese overcapacity. In the last 15-20 years, China has built massive capacity in every commodity, from solar panels to steel. This translates into unbeatable low costs and efficiency, and it makes sense for the world to consume this capacity rather than create more.

Therefore, manufacturing is no longer going to be the biggest driver for job creation in India.

Q. Do you believe automation will change our manufacturing scene rapidly? Also, are there industries where we can complement the Chinese manufacturing capacity?

A. We are already seeing automation coming into our factories — it is not a futuristic concept anymore. Today, if you go to the new automobile plants, or even garment factories, they are bringing in robots because of their efficiencies. Indian factories are getting automated even as we speak, and the jobs being created require engineering and technology labour and not really the mass labour that mass manufacturing might create.

Chinese overcapacity is largely in the area of commodities — steel, copper, nickel, solar panel; coal is also coming up. There may be smaller industries where there is available capacity, but the question is can it create millions of jobs? That’s the challenge for India.

Q. So, where are the jobs for the millions in India going to come from?

A. The typical evolution of jobs as nations develop is from agriculture to manufacturing to services. In India too, agriculture will get more productive and will employ fewer and fewer people. This surplus will enter the workforce, and they will get urbanised and move to the cities. Historically speaking, they should go into manufacturing, but that’s not going to happen.

India’s job creation has to be domestic-led and services-led. The Indian model will be agriculture to services as opposed to agriculture to manufacturing to services. Like in many countries, we may likely never see the full industrial-manufacturing revolution sweep across our country. We will instead graduate to a service-oriented framework.

Q. Will domestic consumption-led services be able to offer incomes to match manufacturing and employ as many people?

A. The challenge with service-oriented jobs is that they typically have low productivity and, therefore, lower incomes, which do not scale up as rapidly as in manufacturing. That’s how it has been so far. But, applying technology to services allows us to multiply productivity in services just like in manufacturing. Domestic-facing, service-oriented jobs powered by technology will be the solution to providing millions of Indians with jobs.

The biggest impact in services will come from the use of technology to improve productivity. The rise of platforms is a great instance of how technology can take services to the next level. Platforms have demonstrated the power to create a lot of jobs without necessarily having an employer-employee relationship. For instance, the several thousand sellers on Flipkart and Amazon and the several thousand drivers on Ola and Uber (Ola recently announced that they would create five million new drivers in five years). While the platforms themselves have just a few thousand employees, they will be able to provide jobs to millions of service providers and consumers.

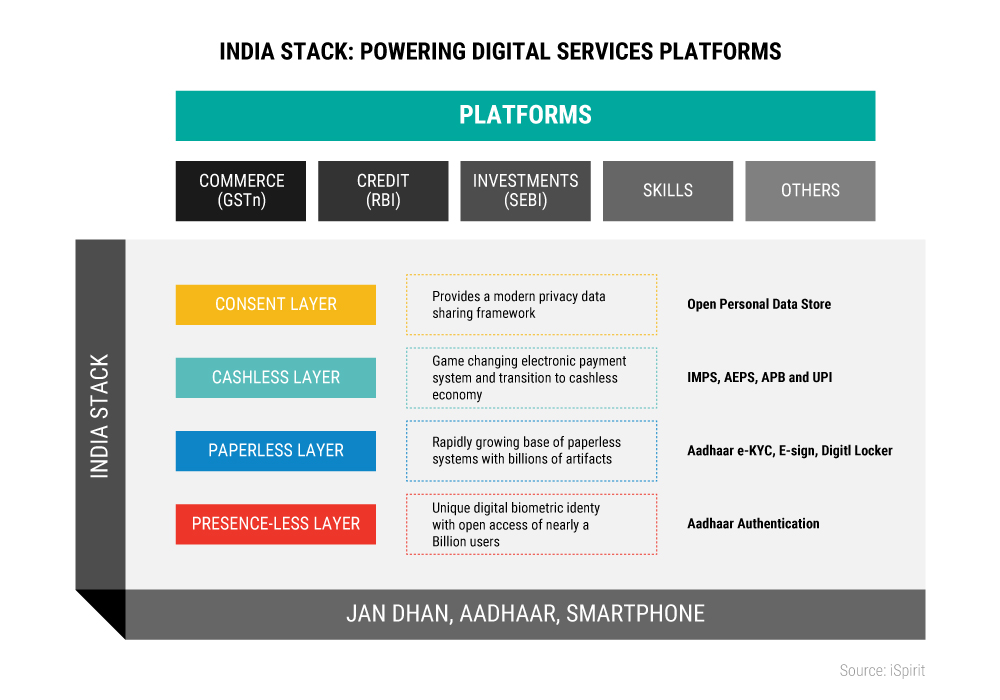

The key here has been the rise of mobile phones and the growing digital infrastructure in the country, which has made it easy to aggregate and connect small, individual business providers with consumers. India’s unique digital infrastructure — the India Stack — that allows for presence-less, paperless and cashless transactions will enable us to make this jump to the next generation of jobs. All this dramatically reduces transaction cost and, in turn, allows more market forces to operate and create platforms. Eventually, this drastic improvement in productivity will translate into incomes that India can leverage for jobs and growth.

Q. What services do you see taking advantage of these platforms?

A. Mobility will be one big thread — a whole system will spring up around it. E-commerce will be another key thread as an increasing number of people are selling through it. Smaller manufacturers and sellers will find a way to address local consumption through these platforms. As retailers get modernised, they will create jobs. Urbanisation too will drive job creation. As a large section of rural Indians move to cities, the task of servicing this urban population will give rise to many jobs. Ultimately, if the right infrastructure is in place, platforms will apply to a range of ecosystems — from farmers, wholesalers, retailers to drivers, service providers, etc.

Q. How should potential job seekers and providers prepare to take advantage of these opportunities?

A. There are two key aspects to note in this new world we are talking about. First, continuous learning is going to be inevitable. Going to college, getting a degree and leveraging that for the rest of the life will become less and less relevant. Knowledge is accumulating exponentially. Therefore, unless you keep learning, you will become irrelevant very quickly. This requires a certain mindset and also access to the relevant learning or knowledge on tap — anytime, anywhere. The concept of learning through classrooms and full-time degrees will continue to exist, but anytime, anywhere learning will start to play a much bigger role.

Second, because of rapid changes through automation, old jobs will phase out and new jobs will be created. So, job seekers need to be agile enough to be able to not just change jobs but also change careers. This requires one to keep reskilling oneself and also consider careers that are fluid and dynamic.

Q. What about the safety nets though? Does this mean that the concept of job security is passe?

A. It is true that when we move to a platform-led economy, the historical social security nets will no longer be there. Today, if you are a formal employee in a company you get EPF (employees’ provident fund) and other social security benefits. However, tomorrow you will need to have a virtual social security net. This essentially refers to greater transparency, financial inclusion and cheaper access to products that offer social security for everyone.

Applying technology to services allows us to multiply productivity in services just like in manufacturing. Domestic-facing, service-oriented jobs powered by technology will help provide millions of Indians with jobs

For instance, a driver who joins Ola will be able to buy a health insurance policy, mutual funds and get access to credit through a platform using his smartphone. His access to credit is not likely to be limited by his assets but be determined by the data on his transactions. This opens up opportunities and social security benefits without the inefficiencies of the past. This requires parallel platform services for social security benefits to emerge in order to support this economy.

Q. You mentioned continuous learning as a key to surviving in this new economy. But how do we enable such learning when there are barriers to access and basic literacy?

A. What we are doing at EkStep is a way to address the challenge of continuous learning. We believe that the future of learning and knowledge lies in mobile phones (and other mobile interactivity devices that may emerge). Some of the earlier learning platforms were replicating the standard learning experience and leveraging static media like desktops. However, learning should be enabled through different interaction media like touch as opposed to just a keyboard. This is especially relevant when you are trying to reach people who are not fully literate and the keyboard doesn’t make sense to them and, instead, becomes a barrier to learning. Touch interface and phones will make learning more accessible and intuitive.

The second important thing is to design the architecture so it works offline too. Once you download the content on the phone, you should be able to disconnect it and use it without any connectivity access.

The third aspect is around assisted learning. While the content is present, it could also be facilitated by a teacher, an adult, a parent or an NGO working in a distributed manner. In this way, learning itself could get platformised and leverage service providers and content to disseminate knowledge in a dynamic manner at a local level.

These rules apply to vocational skills too. For instance, if you want to onboard a seller in Flipkart, there is a process of skilling. He needs to be taught technological literacy, process literacy (order to fulfilment) and customer service literacy, and all of this requires training. Similar rules apply for becoming a driver for Ola. So, one can design skill-based packages that address these needs easily and can be packaged in a platform (delivered over a phone).

Q. How do you see the role of platforms if they are to create jobs without being employers?

A. As a platform, I will think about achieving scale (in millions) and also providing the most seamless experience for both providers and consumers at that scale. If I am a mobility platform for drivers or a delivery service platform for product delivery, I will create support mechanisms and content for all stakeholders (including training material and content on my platform), so they can leverage my platform effectively.

Although the service providers are not employed by the platform, they represent its brand. How the Ola driver behaves reflects on the platform itself. The platform-owner therefore has a brand stewardship issue and has to make sure that everybody who delivers services on their behalf reflects the brand in the right way. Here, processes, training and the product itself, all combine to ensure that the checks and balances are in place.

Q. How do you think the government should approach this? What should their role be?

A. The government is taking a lot of initiatives in this space. We have the National Skill Development Corporation and a lot of the training is being funded by the government. My view is that the training should fund the individual, who should then get a skills voucher of some kind that he/she can produce at any institute and use. I would prefer to fund the individual so that it creates competition among the skills providers and raises the quality of training while lowering the cost.

The current skill programmes are doing a decent job, but given the scale of the challenge we have in skilling people the speed at which we need to be skilling, a lot more can be done.

Subscribe to FactorDaily

Our daily brief keeps thousands of readers ahead of the curve. More signals, less noise.

To get more stories like this on email, click here and subscribe to our daily brief.

Photo: Sriram Vittalamurthy Lead image and graphics: Nikhil Raj P Careernet is the sponsor of our Future of Jobs in India coverage and events. The coverage and the content of the event are editorially independent. For more on how we separate our newsroom and our business functions, read our code of conduct here.