Story Highlights

- In The Lancet study, researchers took diet data from 7,000 Indians, and tweaked the menus to reduce the amount of blue water that went into producing these diets

- They found that minor changes in the menus, such as adding 30gm of red meat per day to one kind of diet, or cutting 10gm of poultry from another, could bring down blue water consumption by enough to stave off a shortage in 2050

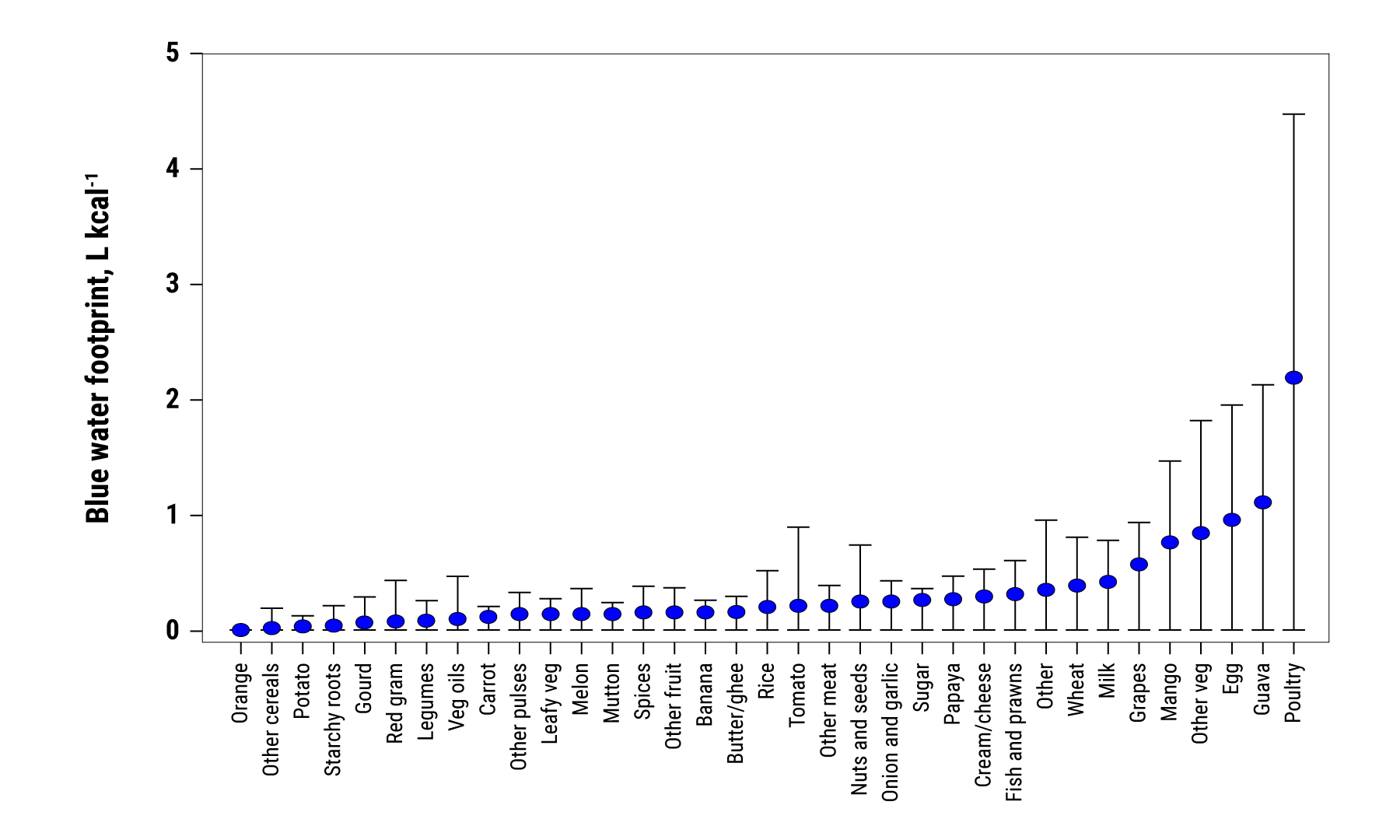

- Overall, the biggest blue-water guzzlers turned out to be poultry, dairy, wheat, and fruits like guava and mango. Red meat, surprisingly, scored well on the water-saving scale

India is the largest guzzler of groundwater in the world. To understand the significance of this dubious distinction, consider the northwestern states of Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan alone. Between 2002 and 2008, around 109 cubic kilometers of groundwater was used up in this region, equal to the flow of the river Godavari in one year.

Such vast exploitation of groundwater has triggered a crisis across the Indo-gangetic plains, with farmers having to dig deeper each year to find water to grow food. And the situation isn’t getting better. With climate change, and receding glaciers, the wells in these farmlands will receive far lesser rainfall and meltwater to recharge each year. The result? By 2050, India’s bread basket could become catastrophically parched.

With climate change, and receding glaciers, the wells in these farmlands will receive far lesser rainfall and meltwater to recharge each year. The result? By 2050, India’s bread basket could become catastrophically parched

Is there a way to stop this? One obvious answer is for Indian farmers to use water more efficiently than they do now. But a set of new studies, culminating in a paper published today in The Lancet Planetary Health journal, suggest that the solution lies in our dinner plates. In The Lancet study, researchers from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) took diet data from a sample of 7,000 Indians, and tweaked the menus to reduce the amount of ground and surface water (together called blue water) that went into producing these diets. They found that minor changes in the menus, such as adding about 30gm of red meat per day to one kind of diet, or cutting around 10gm of poultry from another, could bring down blue water consumption by enough to stave off a shortage in 2050. These changes were also aimed at making the diets healthier, with nutrient intake closer to World Health Organization guidelines. And they brought down the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of these diets, to boot.

Researchers found that minor changes in the menus, such as adding about 30gm of red meat per day to one kind of diet, or cutting around 10gm of poultry from another, could bring down blue water consumption by enough to stave off a shortage in 2050

Indian water researchers say this is exciting new data, because it will help consumers appreciate the link between the food they eat and the water that goes into growing it. “This study is enlightening because it shows that one can adopt changes that optimize nutritional needs, as well as environmental concerns,” Sunderrajan Krishnan, executive director of the Gujarat-based India Natural Resources Economics and Management Foundation, told FactorDaily.

The idea of changing diets to save the environment has gained ground in the past few years. With climate change looming large (discount the reversal of US policy on that front in recent weeks), several studies have found that cutting down on meat and increasing fruit and vegetable intake can reduce both water usage and the greenhouse-gas footprint of European and American diets.

But no data of this sort exists for India.

To fill this gap, the researchers turned to a three-year study completed in 2007, known as the Indian Migration Study, which mapped the diets of urban migrants in Bangalore, Hyderabad, Lucknow and Nagpur, as well as those of their rural siblings. These diets were then classified into five broad categories — rice and low diversity, rice and fruit, wheat and pulses, wheat-rice and oil, and rice and meat, depending on the food items that dominated the diets. Next, these diets were broken down into 36 categories, like cereals, high-fat dairy, poultry and fruit, whose blue-water footprints were calculated to arrive at a footprint for each diet.

To future-proof these diets, the researchers estimated how much each person would have to reduce groundwater use in 2025 and 2050, if the total amount of groundwater for agriculture remained the same as today, despite a population jump of 42% in 2050. They found that the blue water available for each individual would be 18% lesser in 2025, and 30% less in 2050. With groundwater use thus capped, they then altered each diet as little as possible, to arrive at healthy meals that gave every 100,000 people an extra 6,800 life-years. The resulting diets look look like the table below.

The study was funded by Wellcome Trust, as a part of its Sustainable and Healthy Diets in India project.

If Indians do switch to the new diets suggested, those who eat mainly rice and skimp on fruits and vegetables will start eating more of the latter. Those who eat a rice-and-fruit diet will switch from mangoes, which cost a lot of blue-water to grow, to oranges or melons, which don’t. Those who eat a lot of wheat will have to swap some of it for vegetables and pulses, because wheat, an irrigated crop, uses large amounts of blue water. And those who relish poultry will have to swap some of it for red meat, because red meat needs far lesser blue water to produce.

If Indians do switch to the new diets suggested, those who eat mainly rice and skimp on fruits and vegetables will start eating more of the latter

Overall, the biggest blue-water guzzlers turned out to be poultry, dairy, wheat, and fruits like guava and mango. Red meat, surprisingly, scored well on the water-saving scale. According to James Milner, one of the authors of the paper and a researcher at LSHTM, this is because Indian cattle and goats typically graze on rain-fed pasture or are fed crop residues, which don’t need any blue water to grow.

India’s economic growth and the rise in incomes of the last two decades has seen a spurt in consumption of chicken, eggs, milk and pulses.

The study throws up a number of interesting questions. First, is changing diets a feasible strategy for India to tackle its groundwater crisis? In the past, awareness campaigns and public policies have had mixed results in driving dietary changes.

For example, the five-a-day campaign to increase consumption of fruits and vegetables in the United Kingdom didn’t really change food habits even after a decade. A better option, say water researchers, would be to push for better farming practices such as drip irrigation or system of rice intensification (SRI), which cut water usage.

The study throws up a number of interesting questions. First, is changing diets a feasible strategy for India to tackle its groundwater crisis? In the past, awareness campaigns and public policies have had mixed results in driving dietary changes

Not everyone agrees on this, however. According to Veena Srinivasan, a researcher who studies threats to water resources at Bangalore’s Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and Environment (ATREE) , merely altering farming practices won’t take us very far, without a simultaneous shift in diets. Even if farmers grow blue water intensive crops like wheat with lesser water, they are still sticking to crops that are a terrible idea for groundwater-scarce regions, she argues.

While The Lancet study just focuses on tweaking existing dietary staples such as rice and wheat, “the real big change will come if we make a move to millets,” she said. Most millets such as Ragi and Bajra are rain-fed, and do not require blue water. And the shift from millets, which have traditionally been a large part of Indian diets, to wheat and rice is a relatively recent one. This means it won’t be that hard to rewind dietary preferences a little back in time. “You are already seeing this happen in cities which have high diabetes rates, where millets are being promoted at the higher end of the market. If it became cool again (to eat millets), people would come back a full circle. I wouldn’t dismiss that effect,” Srinivasan said.

But if mismatched diet and poor farming practices are two of the reasons behind India’s blue water crisis, the third and biggest one is government policy

But if mismatched diet and poor farming practices are two of the reasons behind India’s blue water crisis, the third and biggest one is government policy. Even if people want to change their diets, and farmers switch to more water-efficient technologies, government policy can feed farmer addiction to ill-suited crops like wheat, pointed out Shilp Verma, a researcher who studies groundwater management at the International Water Management Institute’s Tata Water Policy Program in Gujarat. Policies such as subsidised electricity to farmers in large swathes of rural India and support for water-intensive crops such as wheat, rice, and sugarcane have Indian farmers growing these crops in water-scarce regions. “Food procurement policy decisions are political in nature and have little to do with either GHG emission or water footprint,” Verma said. Before Indian diets change, the distortion of food markets through government policy must stop.

Subscribe to FactorDaily

Our daily brief keeps thousands of readers ahead of the curve. More signals, less noise.

To get more stories like this on email, click here and subscribe to our daily brief.

Lead visual: Nikhil Raj Updated at 10.17am on April 4, 2017, to drop a table and add sources to the remaining three tables.