“Death of a Technology Star”, wrote Bloomberg columnist Andy Mukherjee after the country’s largest software services company, Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), reported weaker than expected earnings on Friday, October 14.

“No, India’s software industry did not die on Friday,” argued former Infosys honcho Mohandas Pai in a reaction piece that appeared on the NDTV website the next day.

So, is the Indian IT sector facing imminent death?

Depending on whom you ask, it’s an over-$110 billion (that’s how much Indian software exports are worth annually) question. The future of the sector, which employs anywhere between three-four million people, is clearly hanging in balance.

This is not the first time Indian IT is facing such a crisis. It has had at least two near-death experiences since it was born nearly 30 years ago. Its last existential crisis was when the global economy crashed after the Lehman Brothers collapse in 2008, and the top customers froze their IT spending. Later, in early 2009, the chairman of India’s (then) fourth-largest software exporter, Satyam Computer Services, admitted to a fraud, sending shock waves across the sector, and raising doubts about the sustainability and governance standards of Indian IT companies among existing and potential buyers.

To its credit, the sector emerged from both the crises.

An existential crisis, third time around

So, why are we suddenly talking about an existential crisis in a sector that continues to show overall growth of double digits year after year?

To find some real answers, I interviewed over a dozen CEOs, board members, employees, outsourcing customers and experts from IT during the past few weeks. While some CEOs blamed their boards and promoters for being too conservative and not allowing the bold steps required to “change the game”, analysts tracking the sector seem to be stuck on outdated metrics doled out by the managements of Indian IT firms quarter after quarter, ignoring the massive disruptions the sector is witnessing. Customers too have changed, say experts.

Meanwhile, chief information officers (CIOs) and IT heads — the conventional buyers of software outsourcing — are battling a crisis of their own. New buyers of technology services are from different functions, not necessarily the IT department. For instance, chief marketing officers will spend more on technology than conventional CIOs by 2017, according to Gartner.

“It is the time to innovate fast or die slowly”

“Quarterly pressures to churn out double digit revenue growth while protecting profit margins make it seem like we’re changing the engines of a 110B spacecraft in mid-flight. But, is there a choice? It is the time to innovate fast or die slowly,” says Chetan Dube, a former New York University math professor who founded IPSoft. The company offers software humanoids to help customers automate their helpdesks and other business processes.

“The IT leadership in India is under the disillusion that it is acting in a derisked manner by taking cautious steps. The irony is that it doesn’t realize that the risk of slow adoption is far greater than the risk of fast transformation,” Dube says.

The disruption is only gaining momentum as traditional buyers and consumers of technology outsourcing are looking beyond incumbent software makers such as SAP, Oracle and so on. India’s software industry has been built primarily on offering application development and maintenance services for large customers deploying software from SAP and Oracle.

Now, even they are struggling. Apple, which is among the top customers for SAP, is now looking to build its own software stacks.

“There is no way our IT Services players can escape the pain. They are caught in a structural change that they can’t escape. Yes, they won’t die,” says Sharad Sharma, founder of Indian software product think tank iSpirt, and former head of Yahoo’s R&D operations in the country.

Is Indian IT facing a wipeout?

The sense of urgency is missing, say experts. “The industry is becoming toast, as I have long been saying will happen. IT companies have been shuffling deck chairs on the Titanic far too long,” says Vivek Wadhwa, a US-based academician and a long-time critic of the Indian IT industry.

“If we wish to survive and thrive in the new world order that is emerging, we have to be bold. We can’t accelerate forward by looking in the rear view mirror,” adds Dube.

The threat of disruption is real. As at least three CEOs confirmed in private conversations with FactorDaily over the past two weeks, nearly half of the existing revenues of IT companies could be threatened by newer technology disruptions and customers’ in-house technology centres.

“Nearly 43% of the current revenues of top Indian IT firms will vanish in the next four years”

“Nearly 43% of the current revenues of top Indian IT firms will vanish in the next four years,” said a board member of one of India’s top software companies, who did not want to be named.

Another disruption is being triggered by a new breed of startups who are offering focused applications on a pay-as-you-go basis. Chennai-based Freshdesk is one such example. Shekhar Kirani, a managing partner with Accel Partners and an investor in Freshdesk, says helpdesk and IT support functions are getting automated fast. “God only help our BPO business and employees. There will be massive job losses,” says Kirani.

While talks of Indian IT’s death are clearly exaggerated, the challenges are real. And like in the case of legendary technology brands such as Kodak and Nokia, most such deaths don’t happen overnight; it’s a slow and painful process.

What’s bringing it on? Disruption, stupid

India’s software exports industry is facing headwinds because of the following factors:

For Indian IT, the new competition is its customers: After years of relying on TCS, Wipro, Infosys and HCL Technologies for their software outsourcing projects, some large clients such as JP Morgan, Bank of America, General Electric, Apple and others are now setting up captive centres. While high-end, high-margin projects are moving away from external service providers, the upside is that India still stands to gain because most of these captives are being set up in Bengaluru.

Yesterday’s disrupters are today’s incumbents (and it hurts): Around two decades ago, India’s software giants challenged IBM, Accenture and HP by offering high-quality, low-cost (a fraction of what it would cost in the US) services remotely. They hired hundreds of thousands of software engineers every year, building dedicated factories of software development for large customers. Now, the low-cost advantage is no more a differentiator. TCS, Infosys, Wipro and HCL are stuck with their bulging armies of software coders who are increasingly becoming irrelevant in the new game. They can’t wish them away, and because of their incumbent positioning, attracting new age, disruptive talent is a challenge.

Is there an Uber of software outsourcing? Conventional buyers of technology services, from banks to telecom companies, want to operate like “a new age Uber” as they prepare to serve and attract the millennial customer. So, the likes of JP Morgan and General Electric (GE) are either doing it themselves, or are partnering with disruptive startups. GE, for instance, is building its own multi-billion dollar software business. JP Morgan is already working with IPSoft. They want to shed the legacy tag, and engage increasingly with disrupters rather than incumbents. On the other hand, new age enterprise consumers of technology such as Uber, Airbnb, Facebook and Google are working with Accenture, and not a legacy Indian service provider.

Crisis in IT leadership: The boards and promoters of large Indian IT companies are too conservative and they lack the bold vision required to build a next generation IT company. They are in “wealth protection mode”, and are not trying sincerely to build the next multi-billion dollar revenue stream. The leadership continues to rely on old metrics of profit margin and revenue growth. The incentive structures are designed to boost profitability, and remain risk averse. IT CEOs’ salaries need to be linked with the volume of new age business won, and not vanilla operational efficiency, but that is not the case.

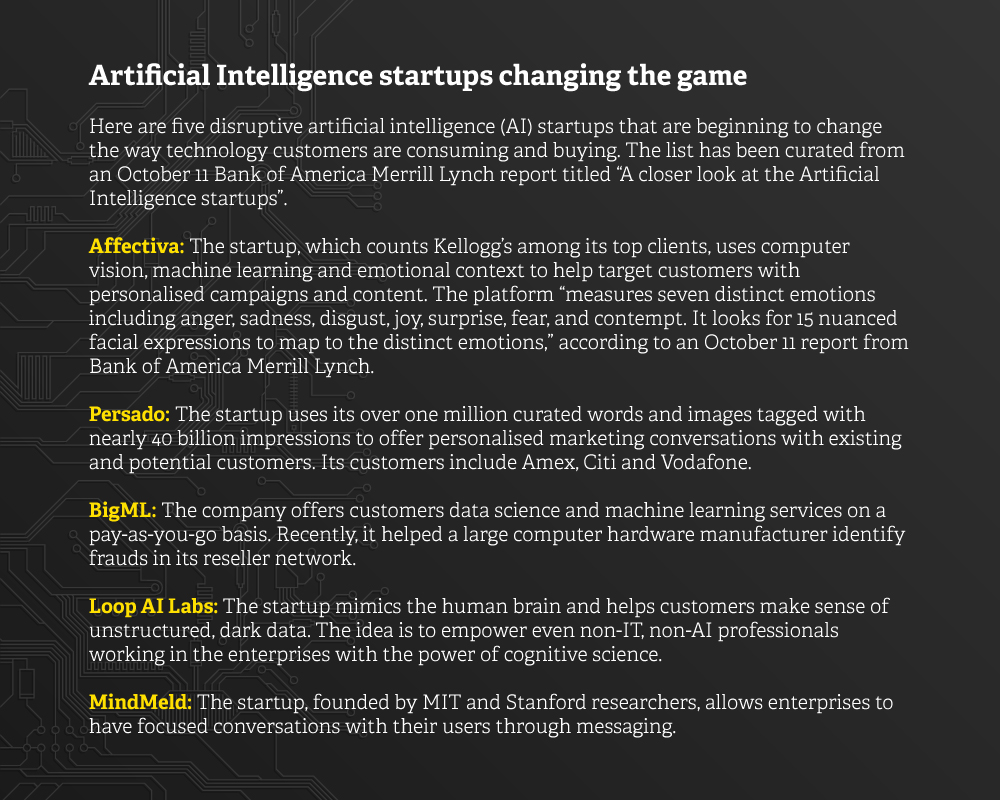

Blockchains, messengers and robots are eating software outsourcing: Technology disruptions have eaten the best and the biggest of incumbents over the years. This time, a new wave of disruptions, including artificial intelligence (AI), messenger bots, blockchains and so on are changing the way customers buy and consume products and services. While almost every Indian IT company has its self-proclaimed version of the next generation AI product, they are more artificial and less intelligent, as I had pointed out in this column for The Economic Times.

The rise of the captives

To understand how far the technology outsourcing game has changed, one needs to look beyond the post and pre-earnings reports published by brokerage houses. While the reports are mostly focused on analysing customer additions, profit and revenue growth in a particular quarter, the larger disruptions shaping the future are not captured adequately. Outsourcing customers setting up their own technology captive centres and moving work in-house is one such example.

San Francisco’s Bay Area is a good place to start with to analyse this trend.

Take five of the most disruptive next-gen consumers of technology in the world today — Facebook, Google, Uber, Apple and Airbnb. These companies don’t buy the low-cost argument at all. If at all they look for cheap service providers, they treat it as a commodity and allow a “chief procurement officer” to make software outsourcing decisions, not an IT head. As my colleague Jayadevan PK wrote a month ago, Apple is already pulling back its high-end outsourcing work to its in-house technology centres. Uber has hired Apurva Dalal as its India CTO who first task is to build a technology captive centre in Bengaluru.

It’s not that these companies are not outsourcing their technology work. It’s just that India’s legacy software companies are not getting a share of the pie, at least not for now.

I spoke to a bunch of company insiders at Accenture and at its rivals to understand who’s getting the business, and why. According to at least two people directly familiar with the work, Accenture, for instance, already does over $200 million of outsourcing work annually for Google. For Uber, Accenture currently does around $50 million worth of annual work, growing at over 30%. Airbnb and Facebook too are Accenture customers.

While Accenture is winning the battle for next-gen IT work, some of the customers such as KLM Royal Dutch Airlines are beginning to shape the future themselves.

In March this year, KLM made an interesting announcement that’s likely to disrupt and reduce the technical support and call centre outsourcing work it so far required. The airline launched its Facebook messenger-based service that allows customers to not only get flight updates, but also to compare options and book their tickets.

On the software programming side, the disruptions are even more pervasive. In May this year, Wired magazine published a cover story entitled “The end of code”. In a world where machines are becoming increasingly intelligent and are beginning to interact of their own accord, the software codes powering them are changing fast too.

“India’s over four million engineers employed in the IT sector have a lot to worry about”

Obviously, India’s over four million engineers employed in the IT sector have a lot to worry about. As pointed out by US-based HfS Research, automation will trim 1.4 million global services jobs by 2021. Of these, nearly 6,40,000 low-skilled positions in Indian IT will vanish, according to the research company.

Get disrupted. Or disrupt by riding the digital wave

The writing is indeed on the wall for Indian IT firms — change fast, or become irrelevant in the years to come.

“In the current environment, there are only two types of companies: the disruptors and the disrupted. So, whether you are large or small, if you have a challenger mindset, the future has never been brighter or more interesting,” says Ravi Venkatesan, former head of Microsoft India, and currently a board member of Infosys.

“First came the wage arbitrage. That is dwindling now”

Dube of IPSoft says India’s software companies are at a tipping point — they could either become victims of their past, or undertake massive overhauls and become future giants in the market.

“First came the wage arbitrage. That is dwindling now. Next came the wave of virtualization, standardization and consolidation. These gains too have reached a point of saturation. Currently, the hormones of digitization are being injected into the IT industry’s lifeline. It is the teen growth spurt years,” says Dube.

The growth curve of digitization is different from any other in the past. “This curve is of a much steeper magnitude. So much so that companies riding on the digital curve will become giants within the next five years, and those that miss the boat will face an existential crisis,” he says.

“By McKinsey estimates, the front-runners have an uplift of 45% in net profits, while the digital laggards have a 35% margin compression. The critical question for all IT companies is where they wish to be on the digital Darwinistic curve,” he adds.

It’s the classic case of “Innovator’s Dilemma”, a term coined by Harvard professor Clayton Christensen. As incumbents, Indian IT companies are struggling to let go of their legacy business. Building a new future can potentially mean loss of business in the interim.

“Organisations we see around today have been built on rigidity, not flexibility”

“Organisations used to working in the old ecosystem must learn to play the new game,” says TK Kurien, vice-chairman of Wipro, the country’s fourth largest software exporter. “Organisations we see around today have been built on rigidity, not flexibility,” he adds.

Experts such as Phil Fersht of HfS Research say the challenge is less about robots and automation, and more about the deeper digital disruption. “The big issue today is that the IT industry is too focused on the wrong things, such as staving off the ‘threat’ of automation and protecting traditional headcount-based delivery,” says Fersht who co-authored the report by HfS in July about the threat robotics and automation poses for jobs.

“IT industry is too focused on the wrong things, such as staving off the ‘threat’ of automation and protecting traditional headcount-based delivery”

Staying alive

Here’s what India’s software giants can do to stay relevant and compete in the new world.

Spend the cash: Infosys, the second largest software company in India, has around $5.3 billion cash in its books. While it’s been acquiring companies since its new CEO Vishal Sikka took over, it’s not helping much. Its larger rival TCS hasn’t made any new age acquisition at all and has mostly spent its cash in beefing up existing revenue streams of back office services.

Overhaul the leadership and the board: Most promoter-driven Indian IT companies are struggling because they are still stuck in the past, chasing profitability and remaining conservative. As a former CEO of an Indian IT firm said, the boards don’t encourage bold moves, especially if this means sacrificing the company’s existing profitability or revenue base.

Acquire the ‘VC mindset’ the right way: A few years ago, both Infosys and Wipro established their venture funds, aimed at picking stakes in disruptive startups. While the intentions were good, the expectations proved to be a challenge. “The questions asked are about how soon can these investments start bringing revenues?” says an executive. By forcing revenue ambitions on these bets, the software exporters are losing an opportunity to shape their future.

Wipro, go private: Among all the Indian IT companies, Wipro is best positioned to go private, get rid of the quarterly earnings circus, and start a massive overhaul. With founder Azim Premji holding over 70% of the company, Wipro can (and perhaps should) become a private company. This will allow it to cannibalise existing revenues, take bold steps for the future and avoid unwarranted scrutiny of short-term investors who are only interested in revenue and profit growth, quarter after quarter.

Subscribe to FactorDaily

Our daily brief keeps thousands of readers ahead of the curve. More signals, less noise.

To get more stories like this on email, click here and subscribe to our daily brief.

Lead image by Nikhil Raj Update: The story was edited on October 17, 2016 at 5:45 pm to add Shekhar Kirani's comments. Another edit was made on October 18, 2016 at 815am to add Sharad Sharma's inputs.