In early 2016, Grofers — a hyperlocal online grocery startup — shut operations in nine cities across the country. Nearly all these cities are thriving commercial centers: Ludhiana, Coimbatore, Kochi, Vizag, etc.

“The smaller cities are not ready for hyperlocal business yet,” declared Albinder Dhindsa, the company’s co-founder. This statement is technically incorrect — commerce in these cities has always been “hyperlocal”. Perhaps, what he meant is they’re not ready for “online hyperlocal”.

Easy payments, access and product innovations are key to overcoming the tough challenges that small-town India poses for e-commerce

Which is not surprising. Building e-commerce in Middle India is hard and requires deep market localization to cater to the heterogenous cultures and habits of its buyers — an inefficient and slow-burn process as we discovered in the second article in this series.

Then there are a handful of issues that are mostly homogenous across small-towns and can be captured in statements like these:

“You want me to pay for it in advance? How do I trust the seller and the product?”

“I didn’t get the OTP. How do I pay?”

“The site never loads on my mobile data”

So, how do you kickstart e-commerce in Middle India where the online infrastructure is consistently poor, discretionary incomes are lower than in metros and shopping is highly contextual?

Cash, card or digital? CoD it is

India loves cash. Small town India, even more so.

Even today, about 70% of all e-commerce customers from the metros — who have adequate infrastructure and trust in the online model — continue to pay through cash on delivery (CoD).

Credit cards are a non-starter (about 24.5 million credit cards have been issued till date in India — a miniscule 2.04% of our 1.2 billion population) and will probably remain so.

Meanwhile, the digital payments stack is rapidly emerging. As this excellent compilation points out, Middle India will likely completely skip the credit card phase and begin to make digital payments through mobiles.

Yet, for all the air time digital payments are receiving, CoD is likely to remain the most popular payment method for Middle India for some time to come.

There are two main reasons for this. One: The digital payments infrastructure is still a long way from being fast, easy and reliable. Two: Consumers are still some way from being comfortable (and trusting) of online payments.

CoD, on the other hand, is smooth and fast (during shopping and checkout), safe (there’s no need to trust payment platforms by sharing payment information) and worry-free (one can return the product if one’s not happy with it or reject it at the time of delivery). With these strong benefits stacked up for CoD, it is difficult to dislodge it as India’s favourite way to pay.

For all the air time digital payments are receiving, CoD is likely to remain the most popular payment method for Middle India for some time to come

While thousands of pincodes in Middle India are still beyond the serviceable zone for CoD, this is changing. From India Post (motivated by its Rs 1,500 crore COD revenue target this fiscal) to private delivery companies, CoD coverage is on the rise. E-commerce companies are building delivery capabilities in-house too, to hike their CoD revenues.

However, CoD is bad news for Indian e-commerce as it involves:

- Additional cost overheads of managing the cash collection network (collecting cash, consolidating it and passing it up the chain).

- A high number of delivery attempts (CoD customers need to be at the delivery location to receive the order) — an average of about 1.25 times.

- A high rate of return (due to wrong product being delivered, fraud or simple change of mind) — as high as 40%.

These issues are unavoidable, though.

Problem or not, CoD is here to stay for a while and companies have no option but to make investments to make the option available to its customers.

Online payments and offline purchases

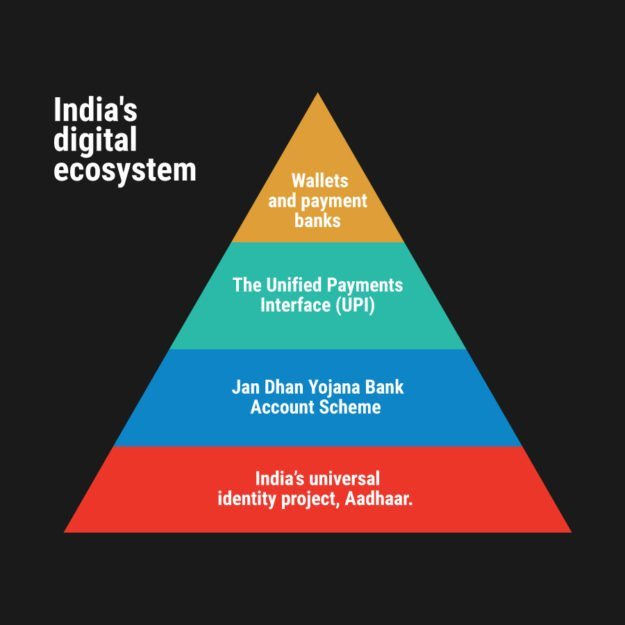

Here’s a 10,000-foot overview of the emerging digital payments ecosystem: At the bottom of the stack is India’s universal identity project, Aadhaar. Above this lies the Jan Dhan Yojana bank account scheme (Current score: ~250 million accounts). The Unified Payments Interface (UPI) — an architecture and a set of standard app APIs by the RBI to facilitate online payments — sits further up, making bank account transfers smooth and seamless. Then there are other parts of the digital payments infrastructure such as wallets and payment banks.

It is likely that the UPI will open up to P2P and micro-business transactions. Wallets are likely to remain relevant in India as they make the payment experience smooth and frictionless.

E-commerce when it concurs with digital payments spells double the complexity for buyers in Middle India as it requires a change in both shopping behaviour as well as in payment behaviour. Which is why the penetration of digital payments is likely to see greater adoption offline.

Take the example of PayTM, India’s leading digital payments company. In September, PayTM announced that its offline merchant base exceeded that of its online base. Innovations to overcome access constraints (like PayTM’s offline payments leveraging the Quick Response Code, a trademark for a type of matrix barcode) could further accelerate this adoption. Vijay Shekar Sharma, founder of PayTM, often shares interesting facts and stories about PayTM’s offline merchant support on social media.

The rising adoption of digital payments is opening up a gold mine for payment providers — data. Interestingly, with more and more customers getting plugged into the digital payments ecosystem, meaningful insights drawn from the increasing cache of data available is helping solve some of the problems of cash-based delivery, including customer trustworthiness (through fraud detection). It may even provide a finer level of user authentication than is in use today, like pincode-level blacklisting, or writing off authentication failures as cost (spurious orders and scams).

‘Your transaction could not be completed’

“We give a 88-98% transaction success rate” — a data point shared by Instamojo, an online payments and collection company, earlier this year in a rare display of transparency in the Indian startup space.

The metric highlights one of the biggest problems with digital payments today — transaction failure rates.

“Payment failure rates are still too high overall,” admits Jitendra Gupta, founder of Citrus Pay, another digital payment solutions startup.

Payment channels like credit and debit cards are especially prone to high failure. Why is that? Gateway providers blame three things:

- Flaky connectivity

- Payment gateway, banks and third-party systems failing to work in sync

- Complex authentication mechanisms

Our mobile data infrastructure sucks in cities and gets worse in smaller towns. Complex, multi-factor authentication mechanisms often fail due to lack of connectivity. One-time passwords sometimes arrive hours after the transaction time is over. Users, overwhelmed by the multitude of steps and with insufficient exposure to such transactions, end up making mistakes. With all this, it would be surprising if the success rates are as high as Instamojo’s.

One simple solution to address the payment failure problem is underwriting customer payments to the merchant and aggregating them for later collection

However, payment failure rates can be reduced through a simpler authentication process, now possible because of the wealth of data becoming available to companies. It’s possible for a consumer to be authenticated instantly based on transaction history.

But, going further, what if payment process itself is decoupled from purchase. “Often consumers want to pay online, but the transaction fails. If you separate the intent from the actual payment process, that solves the puzzle why Middle India is not making payments online,” says Gupta.

One elegantly simple solution to address this problem comes in the form of payment platforms (like Citrus Pay) underwriting customer payments to the merchant and aggregating them for later collection. This allows the shopping experience to proceed without any hiccups. The payment itself can be undertaken at leisure when the users are better connected (a common phenomenon in small towns is brief periods of decent broadband or mobile data access amid long hours of flaky connectivity).

This could work for CoD too and solves one of its problems — micro-collections that are expensive and inefficient. Consolidating collections into larger payments could even enable milk-run type of collections that are more manageable.

Buy now, pay later

In the offline world, customers have access to zero-interest EMIs from NBFCs like Bajaj Finance. This drives a significant portion of large-value purchases — more than one-third of all consumers durables sales gets enabled through such NBFCs.

Easy, instant access to EMIs and personal loans at the time of checkout can go a long way in enabling commerce in small towns.

The restrictions that plague access today, including possessing a credit card, are fast disappearing. NBFCs are already working on offering EMIs (zero-interest) for e-commerce. Besides, platforms like ZestMoney and CashCare seek to provide the layer of authentication required to enable instant EMIs without a credit card.

But truly instant, smooth access to credit will happen only once the window into the data collected from small town consumers opens up. With access to prior purchase patterns, online behaviour and other transactions, user authentication for payments or credit needn’t rely on a long history of credit-worthiness, but rather profiling on the basis of a series of micro-transactions.

As access to credit and deferred payments open up for a large section of the country, the sector needs to be monitored and regulated closely. Especially because sometimes data tracking can get downright creepy and borderline unethical. “Companies can even track whether a customer or a merchant who has taken a loan goes to work. If he or she doesn’t, they’d know that a potential default is on their hands,” said an insider about an online loan provider.

A UX that works even when the internet doesn’t

Given the internet infrastructure and access issues, a lightweight user interface is critical to tap customers in smaller towns and cities. Size optimising of apps is essential. E-commerce platforms still have some way to go in optimizing app sizes (apps range from 8 Mb to 10 Mb today).

If you’ve ever owned a low-cost smartphone with a small internal memory, you’ll know about the frustrating premium it places on app storage space. Plus the cost of downloading it on mobile data.

Perhaps apps aren’t even the way to go? Web apps (like Flipkart Lite) that tie together the lightweight nature of a mobile site with the local convenience of an app may be the answer. This google developer blog highlights some impressive claims that Flipkart Lite has resulted in a 70% increase in conversion and tripled the time spent by users on the site.

But, what if user access to data is so restrictive that even web apps don’t work? Could commerce be more integrated with the device itself and tied to mobile carrier payments?

This is an area Indus OS, a multi-lingual mobile operating system based on Android made for smartphones in India, is exploring. With carrier partnerships for small transaction payments (which don’t need e-mail or digital payment mechanisms), and a homegrown interface that local consumers relate to more, it is looking to alter the fundamental manner in which commerce transactions are accessed. It has a thriving App Bazaar with close to 35,000 listed apps.

Innovations that enable a seamless purchase experience during sporadic moments of internet connectivity are the need of the hour. And media content platforms (the recently launched YouTube Go, for instance) are already working on de-coupling the experience from the need to possess live internet connectivity.

They are doing this by: providing offline browsing access to consumers to the most relevant and in-demand selection in a region; through an asynchronous messaging mechanism that allows conversations with customer service teams or vendors; and a simple payment process requiring not more than a moment’s connectivity (or even better, carrier-enabled underwriting or billing).

Online haggling to win customers?

A common refrain of nearly all leading e-commerce companies is that small town consumers are very demanding. They have little trust and need more information and assurance to be pushed to the transaction stage.

China’s TaoBao has some lessons in this area. T-mall (TaoBao’s e-commerce platform) provides a surreal experience. The product pages scroll infinitely and are loaded with colourful images heavy on sales information. The experience may fail the western benchmark for user experience (UX) but it works because it mirrors how the Chinese shop offline.

This is their key feature: The seller is available on chat for the consumer and is trained extensively on how to make a sale (they’re reportedly given sales tips like “if it’s a young customer, flirt if required”).

Do Middle India consumers want a T-mall like shopping experience? Maybe not. But the clinical western e-commerce interaction funnel may not be the right thing for them either.

What we need is a uniquely Indian interface that mirrors our shopping behaviour. Take for instance, the concept of vendor assuring the consumer about the product quality. Or haggling, an activity that provides Indians the gratification of receiving real-time discounts. These may be difficult to implement in the purchase process, but help build trust.

For e-commerce to win the trust of a consumer segment that relies on such high-context offline shopping, it needs to mimic some of these behaviours.

“The ability to engage in conversations with vendors and platforms through chats and messaging will play a key role in defining the future of e-commerce in small towns,” says Amit Bagaria, VP, business, at PayTM. He believes that this is a sure-shot way to build trust with consumers.

In fact, a significant amount of local commerce (P2P and with micro-businesses) is already moving to messaging platforms like Whatsapp. As we explored in an earlier article, commerce on messaging channels feels more natural (conversational) and also provides for asynchronous interactions.

With the UPI arriving, the friction of digital payments is easing and the value of these channels is likely to explode. A Google BCG report estimates that local P2P payments (the newspaper guy, milkman, insurance agents, etc.) will reach a significant base of 10 million merchants by 2020.

For larger platforms, the ability of merchants to engage with consumers will require feature innovations for both consumers and merchants (like a merchant focussed app that support this) as well as necessary training and support.

Time for an online-offline crossover

Online-offline hybrid initiatives are necessary for improving access. Initiatives like Myntra’s ‘Try & Buy’ (also used by a few other select retailers) allows consumers to touch, feel and experience the product before making a purchase. However, scaling these features purely through an online delivery model may not be efficient.

In this context, it should be pointed out that nearly all e-retailers (Flipkart, Amazon, Snapdeal, Shopclues, etc.) are rapidly integrating India’s vast, unorganised kirana-model to solve the problem of last-mile gaps — a model Alibaba uses to great effect in China — across cities. Their massive expansion would suggest that it’s a model that benefits both the parties and is likely to scale.

Even more relevant, perhaps, are integrated offline-online stores that make e-commerce more accessible to the vast Middle India. There have been some tentative steps in this direction: Flipkart’s experience centers and Snapdeal’s omni-channel initiative, Janus, come to mind.

These initiatives, however, have been limited pilots testing the offline channel in big cities for select categories like mobile phones (surprise, surprise!).

Amazon’s Udaan initiative appears to be a bolder, larger step in this direction. As part of this initiative, the global e-commerce giant is partnering with small traders across the country to open up Amazon-branded ‘Udaan points’ that are offline fronts for customers to order, pay and pick up items from Amazon’s selection. It has partnered with Storeking, a startup with close to 10,000 outlets in rural (predominantly south) India, and has also signed a deal with the Rajastan government for opening up 36,000 Udaan stores in the state.

The trouble with such initiatives is that it may be financially untenable for e-commerce companies to support both online and offline models without fully scaling one or the other. However, they can help open up access and bring a significant number of new consumers who could potentially graduate to discovering and buying online.

Let data drive the show, and be patient

From personalisation to smoother payments to responding to customer complaints, data will play an increasingly bigger role in the online purchase journey as e-commerce seeks to create diverse need-based experiences while smoothening out the creases.

India’s consumer behaviour is on the verge of becoming data-rich, especially as the digital payments layer begins to take effect in the offline world. This will, in turn, help e-commerce’s foray into Middle India while keeping in place a critical aspect: the efficiency required for the long grind.

Middle India’s untapped fortunes are fast becoming a popular narrative. And not without reason — there is a huge market out there that still lies unorganised and accounts for most of the retail in the country.

Yet, any assumptions about a large market waiting to be tapped instantly needs to be erased. Middle India needs some fundamental changes like better-paying jobs, improved infrastructure and rise in the quality of life before it jumps online to shop. Building e-commerce innovations before these changes take place would be farcical.

Middle India’s untapped fortunes is fast becoming a popular narrative. It isn’t wrong — there is a huge market that still lies unorganized and accounts for most retail in the country

Therefore, anyone looking to address this market needs to be led by data, be willing to take on a long journey in line with the ecosystem and not be motivated by rapid Silicon Valley-type scaling dreams. Patience, and slow, cumulative growth will be critical, although the value of disruptive innovations will be immense.

Will new local players emerge that can better customise the shopping experience and be more nimble in smaller markets? What can they do different from the many hyperlocal firms shutting shop? Can players like ShopClues, who are building themselves up for this market and potentially have some heft, emerge stronger and more resilient in the long run? And will this eventually lead to another round of consolidation on a later stage?

These are open questions for whose answers we’ll have to wait and watch.

Subscribe to FactorDaily

Our daily brief keeps thousands of readers ahead of the curve. More signals, less noise.

To get more stories like this on email, click here and subscribe to our daily brief.

Lead image: Anu John David Disclosure: FactorDaily is owned by SourceCode Media, which counts Accel Partners, Blume Ventures and Vijay Shekhar Sharma among its investors. Accel Partners is an early investor in Flipkart. Vijay Shekhar Sharma is the founder of Paytm. None of FactorDaily’s investors have any influence on its reporting about India’s technology and startup ecosystem.