It’s the company’s sixth anniversary party, and HasGeek House is thrumming with activity, though it’s nowhere near as busy as it’s going to get in a couple of hours. People walk in and out of the small independent house in Bengaluru’s Domlur area that serves as headquarters for HasGeek.

On the top floor of the narrow house, in a room carved out of what used to be a terrace, Amelia Andersdotter, a 29-year-old Swedish politician, internet privacy activist and one-time member of the EU parliament, is giving a talk on the Swedish Pirate Party and its tumultuous history. The room is full of geeky men (yes, those stereotypes are unfortunately real, even though one of HasGeek’s co-founders is a woman), and the air is thick with questions about privacy, internet security and the differences between European and Indian privacy laws.

The room is full of geeky men, and the air is thick with questions about privacy, internet security and the differences between European and Indian privacy laws

On the ground floor of the house, two-and-a-half-year-old Amal Zaiki, dressed in a frilly pink frock, sits at a worktable and meticulously finishes a bowl of noodles while her mother, Zainab, talks to guests and coordinates food delivery for the party, which is getting larger by the minute. By the time Andersdotter has finished her talk and trooped down along with the audience, the ground floor of the house is full of people — at least a hundred have crammed into the small rooms and more have spilled over onto the stairs, kitchen and garden area. These are all geeks of one colour or the other — startup founders, developers at startups and established tech companies, freelance coders, design students, UI-UX designers, data and security experts, a tech journalist or two...

The audience

at MLR Convention hall, Jayanagar, Bengaluru during a HasGeek

conference

The audience

at MLR Convention hall, Jayanagar, Bengaluru during a HasGeek

conference

Of conferences and conversations

But what is HasGeek? Chances are, unless you belong to the communities mentioned above, you’ve not heard of it or its founders, Kiran Jonnalagadda and Zainab Bawa, or have only a sketchy idea of what HasGeek does — like I did till I first met the duo a few months ago.

I found out that the bootstrapped company, started in 2010, organises some of the best technology conferences in India, built around themes such as developer operations (Rootconf), front-end engineering and design (Meta Refresh), data and analytics (Fifth Elephant, named after the invisible elephant in Terry Pratchett’s Discworld novels), Javascript (JSFoo), and Android (DroidconIN, part of a worldwide series of conferences focused on the Android ecosystem).

There will be two new ones in 2017: one on digital payments (50P Conference) and the other on scientific nutrition and “body hacking” (Kilter Con). There are also many smaller events, usually non-ticketed — hackathons, language-specific seminars, workshops, talks and social-impact events — that are organised or facilitated by the company. There’s an Open House every Friday, with a fridge full of beer and snacks on the table. Techies and other friends of HasGeek can walk in, grab a beer, and hang out with a variety of people with different passions — technology, writing, entrepreneurship; even feminism and social change.

Zainab

Bawa and Kiran Jonnalagadda at JSFoo, 2016. Image: HasGeek

Zainab

Bawa and Kiran Jonnalagadda at JSFoo, 2016. Image: HasGeek

Apart from this, HasGeek also runs a jobs board called HasJob which sees hundreds of companies (mostly startups) and applicants from the tech community across India posting requirements every month.

All this is run by Zainab and Kiran with a team of 17 people and an army of volunteers.

Running six major, multi-day, curated tech conferences — for which speakers are handpicked by an editorial board, taken through their paces, and rehearsed for at least three days; the entire process overseen by Zainab — is hardly a cakewalk.

But, Kiran and Zainab’s achievement and influence are far larger: they help synergise a scattered tech ecosystem without being involved in the business of tech themselves; they bring geeks and tech aficionados together and give them a non-competitive space to talk about things that excite them — the latest programming language or the newest app development platform — and they do this with rigour, efficiency and integrity.

A midnight

hackathonImage: HasGeek

A midnight

hackathonImage: HasGeek

They have no stake in the ecosystem apart from starting great conversations, bringing technology solutions to the table, and bringing together people who can create great technological change in India

They have no stake in the entire ecosystem apart from starting conversations, bringing technology solutions to the table, and bringing people who can create great technological change in India together. They earn a living from this, but they have no ambition to discover the next great startup or become a unicorn or get funding for themselves or for other entrepreneurs.

“I find engineers at ease in their conferences, and that’s not a trivial thing. There are some conferences where techies are not comfortable. There’s too much marketing talk, the technical quotient is not up there,” says Amod Malviya, co-founder, Udaan, and former CTO of Flipkart, who has attended and spoken at many HasGeek events.

“In these conferences, you are judged by the power of your idea, which is different from a networking conference. Even when I was in Flipkart, I didn’t wear the CTO hat; I was just another engineer in a community of engineers. There are many small things they do that make people feel at home, and this shows up in the kind of comfort people have exchanging points of view and ideas,” adds Malviya.

The year 2017 is slated to be a big one for HasGeek. It’s gearing up to make its first acquisition — quite an achievement for a small, bootstrapped company within six years of its founding. The company being acquired, Belong, is a neighbourhood communities startup founded by Aravind RS and Gaurav Srivastava.

HasGeek is gearing up to make its first acquisition — quite an achievement for a small, bootstrapped company within six years of its founding. The company being acquired, Belong, is a neighbourhood communities startup.

HasGeek was looking to build something similar to Belong to facilitate conversations at HasJobs and for speaker-audience interaction. Aravind, who had been a speaker at one of its conferences, was known to Kiran and Zainab. "Acquiring the technology will save us about a year of work,” says Kiran.

A speaker at

Fifth Elephant, 2016 edition. Image:

HasGeek

A speaker at

Fifth Elephant, 2016 edition. Image:

HasGeek

They are adding a new event to the roster later this month: 50p, a conference on digital payments, which is bound to be super-relevant in the wake of demonetization and increasing government insistence on going cashless.

The two also have a very geeky approach to fitness, and have been adherents of the keto diet for over a year now. Not used to doing things by half measures, and big fans of the quantified self, the couple is now organising an event in April around improving one’s body through better nutrition, fitness and habits, called KilterCon. The keto diet will feature in a big way, one assumes.

All this wouldn’t have happened if two remarkable people from two completely different worlds — one a self-taught coder, a Telugu boy from Bengaluru who dropped out of school; and the other a serious academic from a Muslim business family in Mumbai working on a PhD in the politics of land ownership — hadn’t met in the early 2000s.

Those who have known Kiran for a long time marvel at the change in his personality. Known as “Jace” to most people, he was a shy, intensely nerdy kid who loved computers and coding more than being around humans in real life

Those who have known Kiran for a long time marvel at the change in his personality. Known as ‘Jace’ to most people — a contraction of his full name, Kiran Chandra Jonnalagadda, or JC Kiran in school — he was a shy, intensely nerdy kid who loved computers and coding more than being around humans in real life, says Gourav Jaswal, who has known Kiran for 20 years and gave him his first real job as a writer at CHIP magazine. “Do people call him ‘Kiran’ now?” Jaswal sounds mildly surprised. “Back then, everyone used to call him Jace, including his dad. Only his mother and I called him Kiran.” Jaswal is the founder of the Goa-based startup incubator Prototyze.

While he was still at school, Kiran hung out with people twice his age on early internet forums such as the bulletin board service (BBS) called CiX. This was perhaps India’s first BBS, started by Open Source evangelist the late Atul Chitnis, who was one of the mainstays of India’s first Free and Open Source conference, FOSS.in (formerly Linux Bangalore). [Read about CiX and how it spawned one of India’s earliest and longest-living mailing lists, SilkList [click here.]

A CHIP

magazine cover from the late 90s. Image source: @tushargok on

Twitter

A CHIP

magazine cover from the late 90s. Image source: @tushargok on

Twitter

Most people who met ‘Jace’ were surprised to find he was actually a young boy. By then he had already developed an abiding love for open source software, and admits that he had a deep disdain for things like marketing and structured companies. “For me, software was the purest thing — and it was ruined by marketing. Windows was an inferior product that had done well because of marketing, and Linux was a superior product that nobody used because it wasn’t marketed,” he says.

He has gradually changed his stance on this. “But, at that time, I was in the middle of my rebel’s education, and marketing was a bad word.”

Rebel’s education is accurate. In 1998, he dropped out of his pre-university class (or PU; the equivalent of Class 11-12) and made his way to Mumbai. He had written an email to Jaswal, who was the editor of CHIP, saying he wanted to work at the magazine — it was one of the few havens at that time where a geeky kid could hang out with people who spoke the same language — and was with the magazine for over a year, writing and creating technology for it.

A participant

at DroidConIn, 2016. Image: HasGeek

A participant

at DroidConIn, 2016. Image: HasGeek

“CHIP magazine struck a chord with nerdy kids. I used to get 40-100 emails a day, the vast majority from young people, many studying in engineering colleges, who wanted to meet us, talk to us,” recalls Jaswal. “Kiran wrote to me saying, ‘can I come work with you?’ He was the poster child for a computer geek. He might have been below the legal age to work.”

Kiran was 17 years old. Nevertheless, he got the job, mainly because Jaswal felt he had “a formidable mind”: “He would write very precisely and with great authority on matters of technology. A lot of people I respect say he is one of the best technologists they have known.”

A lot of people I respect say he (Kiran) is one of the best technologists they have known — Gourav Jaswal, former editor of CHIP

A few months later, his mother called Jaswal and said Kiran hadn’t finished his PU degree and still had a paper to clear and could he please make sure that he came back and took it? Kiran cleared his PU after five attempts and never earned another formal degree in his life, although he was a technology consultant for two educational institutions in later years — the Institute of Bioinformatics in Bengaluru, where he designed the database, wrote most of the code, and built a technology team for the Human Protein Reference Database, and at the Institute of Genetic Medicine at Johns Hopkins University in the US, where he continued the work he had done at the former.

Although Zainab doesn’t seem to wear a religious identity on her sleeve, many of her writings over the years reflect her deep introspection over this identity

Meanwhile, Zainab was studying in Mumbai, majoring in sociology and anthropology, and simultaneously working as a researcher and activist on issues of urbanism and governance. She worked with Praja Foundation, a non-profit working in the area of accountable governance, in Mumbai on developing a handbook for citizens on urban governance; lived in Kashmir during an extremely violent period, doing research on youth, violence and conflict; and was part of the well-known Sarai project at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) in New Delhi, arguably South Asia’s most prominent platform for research on the transformation of urban spaces, especially the intersection between cities, information, society, technology, and culture.

Zainab comes from a Kutchi Muslim family of business people. Although she doesn’t seem to wear a religious identity on her sleeve, many of her writings over the years reflect her deep introspection over this identity — especially in a series of posts on the website Kafila.

In one of the posts entitled ‘In the midst of blasts and fireworks across cities…’ in 2008, she wrote: “As there is no ‘city’ in the sense that we each make our own city and carve our own niches... so also there is no one universal feeling of vulnerability. Let me lay out some of the many vulnerable feelings that I feel from time to time these days: a). Being a woman in a live-in relationship with my boyfriend and a strange battle that has been going on between my mind, my boyfriend and his family; b). Being somewhat unemployed and attempting to work through meaningful relationships rather than work for money only (and that darn inflation); c). Taking the courageous risk of getting a house for myself in this city in the middle of my unemployment, an act that I am experiencing as a leap of faith, sometimes a great feeling and sometimes a scary feeling; d). The destiny of being Muslim at a time when bombs burst in Bangalore and Ahmedabad and who knows where else …; e). Figuring out the law and rules and regulations concerning various things and various relationships in a city whose language, both spoken and unspoken, I am still figuring out (what if I make mistakes …)..”

Zainab and Kiran first met through the mailing lists for Sarai and the Sarai Reader, a collection of research publications by Sarai Fellows.

Zainab and Kiran first met through the mailing lists for Sarai and the Sarai Reader, a collection of research publications by Sarai Fellows. Kiran had applied to Sarai for a new media fellowship, and was added to the Sarai Reader mailing list. They started dating when Zainab moved to Bangalore in 2006, to pursue a PhD at the Centre for the Study of Culture and Society on how land acquisitions in Indian cities for infrastructure development is impacting the economic lives of ordinary people. Around the same time, she was also a research fellow at the Centre for Internet and Society, and writing for online journals such as Kafila.

Kiran had taken up a consulting position with Comat Technologies — and he had his first brush with the government and government policies while working on the Karnataka government’s Nemmadi Project. Nemmadi, or the Rural Digital Services project, was started in 2004 as a project helping give rural citizens access to governance through telecentres, to help them with issuance of certificates such as death/birth, caste, income, residence; and to access state benefits. This was done through a public-private partnership model, with Comat Technologies as the private partner, and Kiran was responsible for coordinating with the technology team that operated 800 computerised centres in villages.

Meanwhile, he had also been active on the Bengaluru Open Source scene, and was a part of the Linux Bangalore (subsequently FOSS.in) events. Open source held exciting potential but the general feeling was ‘how can you guys with your free software be better than an entire industry?’ says Kiran. “For us, these events were like a huddle corner because the outside world didn’t take us seriously. We needed a space where we could discuss the hardcore technology of Linux without having to constantly defend Linux... where we could feel free to speak up and not be criticised.”

Open source held exciting potential but the general feeling was ‘how can you guys with your free software be better than an entire industry?’ - Kiran.

At the same time, he felt that the FOSS.in events were a bit too structured and too conscious of the speaker-audience divide. “There was almost a class division between the speaker and the audience. It was not a forum of equals,” he says. Wanting to break that wall, in 2006, he and a few other open source enthusiasts like Thejesh GN, co-founder of DataMeet, organised Bengaluru’s first Barcamp — user-generated “unconferences” for people to share and learn in an open environment. Zainab was an attendee and volunteer at some of them.

First Barcamp

in Bengaluru, April 2006, during a talk by Pete Deemer at Yahoo!

office

First Barcamp

in Bengaluru, April 2006, during a talk by Pete Deemer at Yahoo!

office

But after a few iterations of the non-profit Barcamps, Kiran started feeling that the quality of the talks could be improved. This was the time when TED Talks started becoming popular in India, and he was massively impressed by the quality of the talks and how they were documented and preserved. He felt that by their very looseness of structure and somewhat casual attitudes, Barcamps were losing out on institutional knowledge.

Finally, in 2010, HasGeek was ready to take shape. Its first conference was in October 2010, at the IIM-Bangalore campus, on the topic HTML5. Unbelievable as this sounds today, Kiran had immense difficulty finding sponsors for this event — because no one was interested in developing better websites! The whole domain of website development and browser-based applications had stagnated — Kiran believes this was because of the dominance of Internet Explorer — but the scene was changing because Chrome had arrived.

The whole domain of website development and browser-based applications had stagnated but the scene was changing because Chrome had arrived

Given the lack of enthusiasm from sponsors, Kiran finally decided to put in the last of his savings — Rs 50,000 from a tax refund — and go ahead with the event (in the last minute, Microsoft plonked down some money for one of its evangelists to come and talk to an “outside audience” as a sponsored talk.) This conference, named DocType HTML5, went on to have five iterations in as many cities in India between October 2010 and February, 2011.

DocTYpe HTML5

event in Pune in December 2010

DocTYpe HTML5

event in Pune in December 2010

HasGeek’s first event on Android took place in April 2011, and the company was on a roll, with four events in 2011.

Zainab, who had been an attendee and occasional volunteer at the Barcamps, had a big role to play in the way HasGeek evolved. Though initially, her job was mainly to provide logistics support, soon she was approaching people for sponsorships, screening speakers, and deciding the flow of the events.

But idealism is not execution, nor is it a business. My response to problems is to solve them through technology. Zainab knew how to run an actual business — Kiran

“In Zainab’s hands, it became a big, more business-like organisation. I’ve always been somewhat of an idealist. I have ideas about how communities should exist,” says Kiran, who is a bit obsessed with community dynamics and has written extensive blogposts on different online communities and how they stack up against each other — from blogging platform LiveJournal (he was the first user from India) to the Sarai Reader mailing lists.

“But idealism is not execution, nor is it a business. My response to problems is to solve them through technology. Zainab knew how to run an actual business, financially and as an organisation. She had the people skills, and the ability to set up an independent editorial team that would identify and vet speakers,” says Kiran, who wrote the code for a ‘talkfunnel’ — an online programme that lets potential speakers propose talks and participants vote on them. This architecture is freely available on Github, and conferences (such as The Goa Project) and several companies use it for free to select speakers for their own events.

“I also have strong interests in pedagogy, which is why I have taken up editorial very passionately at HasGeek,” says Zainab. “This combination of thinking-doing and hustling worked very well for us in the early years of HasGeek, when we were trying to establish proof of concept.” The combination of passion for technology and a rigorous, academic approach to the curation of speakers sets HasGeek events apart from similar events across the tech ecosystem in India. For instance, they don’t just approach the well-known “talking heads” or “thought-leaders”. More than 600 previously unknown speakers who had never stepped on a stage in their lives, have presented at HasGeek conferences. Several have gone on to become trainers.

One of the things they are proudest of is the independence of their editorial process, which they have rigorously maintained, despite the events being sponsored by corporate entities. “Even though there are paid speaker slots in our conferences -- and this is clearly mentioned in the programme -- if someone is paying to be a speaker and isn’t good enough, they are categorically rejected,” says Zainab. Even for sponsored talks, if the main intention is to promote a product or company, it’s unacceptable. It has to benefit the community.

"Functionality is an asset, but code is a liability," Kiran says, when I ask him why he does what he does. One of the reasons, he says, is to make sure that the community of Indian developers, and the companies they work for, share the liability of maintaining and updating code. "The maintenance cost of software is higher than its development cost," he adds.

"Functionality is an asset, but code is a liability," Kiran says, when I ask him why he does what he does. "The maintenance cost of software is higher than its development cost."

“The work they are doing is absolutely magical. It is very, very important to the ecosystem. I am a big supporter and champion,” says Sharad Sharma, co-founder and governing council member of iSPIRT Foundation, the well-known software industry body and think-tank. “What they do is they bring expert technology practitioners to share their work with novice tech practitioners, and do it in a fairly selfless fashion, in a way that’s focused on social good and lifts the whole ecosystem up.” Sharma feels HasGeek’s work is in some ways complements iSPIRT’s work, which provides business support to the tech and startup industry to HasGeek’s technology support.

November 10, 2016. It was the first day of DroidConIn, a global conference for Android developers conducted in India by HasGeek. We were in the middle of a panel discussion on women in tech, moderated by Zainab. Towards the end of the talk, Amal, Kiran and Zainab’s 2.5 year old daughter, who was sitting in the front row of seats, showed signs of wanting to go to her mother. Someone held her up on to the stage and Zainab picked her up and kept talking, without dropping a single beat, as if it was the most natural thing in the world.

Zainab and Kiran’s

daughter, now almost 3, has been a constant presence at HasGeek events and at

their office. Image: HasGeek

Zainab and Kiran’s

daughter, now almost 3, has been a constant presence at HasGeek events and at

their office. Image: HasGeek

To her, it IS the most natural thing in the world. It also seems, to me, a perfect example of how the couple has blurred the boundaries between ‘work’ and ‘life’. Zainab believes that the exclusion of children from serious, adult spaces often makes us forget that someone, somewhere is taking care of them -- and it’s usually the mother. She feels it makes it easy for men in technology and other careers to not take up full responsibility as parents in favour of the more traditional role of ‘breadwinner’, and this is a loss for them, their children, their spouses, and for society. So, they have decided that all their conferences -- starting with the aforementioned DroidCon in November 2016 -- will have childcare centres equipped with toys, books, and an adult supervisor, so that mums and dads don’t have to miss the event because they couldn’t find anyone to babysit the kids.

Starting at a

conference last year, HasGeek has been creating child-care rooms at all the

venues where parents can leave their kids while they are attending

talks

Starting at a

conference last year, HasGeek has been creating child-care rooms at all the

venues where parents can leave their kids while they are attending

talks

Zainab tells me (and I remember this from the sixth anniversary event as well) that Amal is always at the office, and colleagues often babysit her when both parents are out on meetings. “Amal has been with me during sales meetings, interactions with clients, at conferences and every moment. People may have been uncomfortable initially, she says, but over time they just got used to having meetings where Amal was being fed. “This has helped me appreciate the struggles that working mothers go through when raising a child and picking up their own careers.”

Initially, I'd have to find ways to excuse myself to go elsewhere to breastfeed her (Amal, her daughter). Subsequently, I'd just start feeding her during meetings and conversations — Zainab

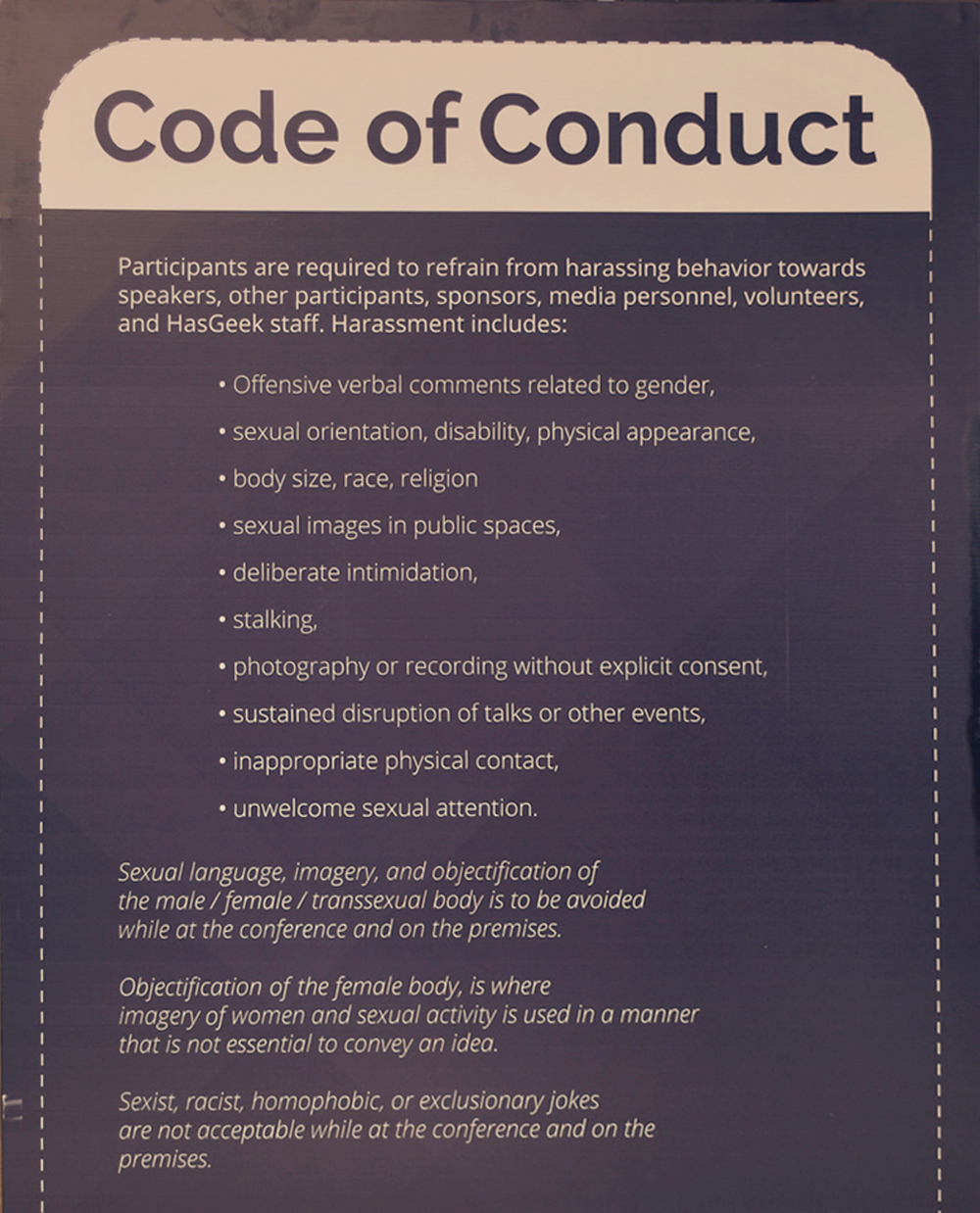

These strong feminist beliefs shared by the couple have led them to consciously enable women to take part in tech conferences (which are usually overwhelmingly male) even if it means laying down certain ground rules that clearly spell out behavioural expectations. For instance, this notice is displayed prominently at all the events. These may seem like small measures, but they signal a refreshing change in culture.

This code of

conduct notice spells out behavioural expectations at all the

conferences

This code of

conduct notice spells out behavioural expectations at all the

conferences

Both partners have been exploring larger social issues along with their work. While Zainab collaborates on projects at the intersection of feminism and the digital world (such as this one) Kiran, who has always been a vocal supporter of internet privacy, net neutrality and free expression, has emerged as one of the strongest voices in the Indian internet space on these issues. He is the co-founder and volunteer trustee, along with other activists/writers like Apar Gupta, Aravind Ravi Sulekha, Karthik Balakrishnan, Nikhil Pahwa, Rachita Taneja, Raman Jit Singh Chima, and Rohin Dharmakumar, of the Internet Freedom Foundation, a not-for-profit organisation that aims to create research-backed support for online freedom and democracy and engage with the government in matters of policy and regulation. The foundation emerged from a more rag-tag collective, created mainly by forging connections with other like-minded people on Twitter during the savetheinternet.in campaign, which saw a big win in 2016 in upholding net neutrality in India when it forced the telecom regulator TRAI to hold an online public consultation on net neutrality during the Airtel zero-rating case. The collective was also vocal during the debate over Facebook’s Free Basics

This is possibly one big step in Kiran’s evolution from geek to activist.

“I find it very hard to pin my identity to something - say that I am a programmer and that’s my identity. I do not have an academic education. I love technology, but it’s like language... when you get good at that language, it becomes a means of expression. But I am spending more time on the Internet Freedom Foundation now, finding ways to engage with the government and policy,” says Kiran. His paper ‘A Rant on Aadhar’ was widely circulated among policy-makers in Delhi recently.

The only criticism they have faced, at times, is for not “thinking bigger”. Sharad Sharma articulates this as a failure to “ride the thermal” (a reference to the atmospheric phenomenon) of technology innovations coming from India and globalising them. “The only difference we have had is over this... every new technology has come from the west. This is the first time we have technology trends starting in India,” says Sharma. “HasGeek did the JuliaCon in 2015 (on the programming language Julia), and now Julia conferences are happening everywhere in the world. My push to them has been to take JuliaCon everywhere, and instead of riding foreign thermals coming into India, embrace India thermals. That option has been missed in Julia. That option was missed in UPI. They did a hackathon on UPI in February 2015, before others. But in one year, UPI has gone mainstream.”

He wants them to “make earlier bets, take risks, catch a thermal in its infancy.”

In fact, even as we speak, HasGeek, which is furiously gearing up for its upcoming payments conference, 50P, has locked horns with iSPIRT over IndiaStack, which is backed by iSPIRT, that can potentially help developers create solutions for India’s digitally underserved. But Zainab and Kiran are not convinced about its security and privacy aspects.

It’s a sign of a healthy ecosystem, though, that such fights don’t devolve into personal acrimony but remain in the sphere of ideas and data.

Because data and ideas are, after all, like the invisible but omnipotent fifth elephant in Pratchett’s universe -- the oil that lubricates the digital world.

Correction: An earlier version of this story said 50p conference will be held in April. It will actually be held on 24-25 January, 2017. The story has been updated with this information.

Correction: The story publishing date was initially wrongly mentioned as 'January 16, 2016' instead of 'January 16, 2017'. This has now been corrected

Updated on 17.01.17 at 5.40 pm: A previous version of this story erroneously mentioned that the company HasGeek is acquiring was earlier called Scrollback. However, subsequent information revealed that the company is called Belong, and it has no association with Scrollback. The error is regretted.

Correction: IndiaStack is not 'a set of open software protocols' as earlier mentioned, but an open API project.

Lead visuals by: Nikhil Raj

Zainab and Kiran’s

daughter, now almost 3, has been a constant presence at HasGeek events and at

their office.

Zainab and Kiran’s

daughter, now almost 3, has been a constant presence at HasGeek events and at

their office.