Earth is vastly overpopulated. Food is scarce. So is fuel. Drinking water even more so. Governments have become tools of giant corporations. The world is divided into the haves and have-nots. And the best news of all: globalisation has triumphed, capitalism has delivered on its promise of a hyper-consumerist market-driven world, which runs on marketing and materialism and is controlled by advertising agencies. Copywriting is by far the most well respected and best-paying profession (finally!).

Welcome to the world of The Space Merchants.

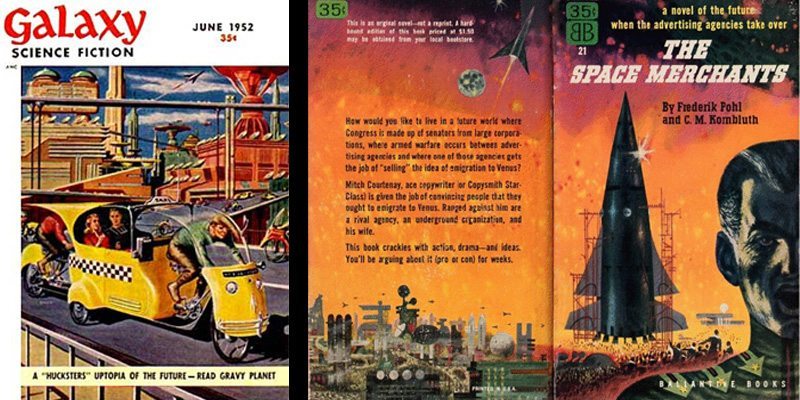

Written by Frederik Pohl (drawing from his experiences as an ad man) and Cyril M. Kornbluth and first serialised in the Galaxy Science Fiction magazine as Gravy Planet with the tagline, ‘A huckster’s utopia of the future,’ The Space Merchants was published as a single book in 1953, as ‘A novel of the future when the advertising agencies take over.’ At once a satirical take on capitalist consumerism, a dystopia, an extrapolation of global trends that have only accelerated since it was written, a story of the evolution – and devolution of – technology, a cautionary tale against the perils of unregulated advertising and crass commercialism, a tale of corporate espionage and rivalry, and a thriller that just about manages to deliver on its suspense, The Space Merchants is rightly considered a science fiction classic and included in the SF Masterworks series. And for all of that it clocks in at just about 200 pages.

Our narrator is the chief protagonist (antagonist?) Mitchell Courtenay, copywriter — sorry, Copysmith, Star Class — who works at one of the two advertising agencies that run the world: Fowler Shocken Associates, whose recent triumphs include turning India into Indiastries, a whole subcontinent merged into a single manufacturing complex (perhaps the world’s first corporate state), and testing a system that projects advertisements directly into the retina of the eye.

In Mitch’s world, overpopulation is a great thing (even if people are paying rent to sleep in stairwells), and the steady dumbing down of the populace with a steady diet of intrusive media and ubiquitous advertising is even better. Because, “increase of population was always good news to us. More people, more sales. Decrease of IQ was always good news to us. Less brains, more sales.” And to generate sales, the ad agencies will do anything, even add addictive substances to the products they sell. Nothing harmful of course, merely habit-forming.

In Mitch’s world, overpopulation is a great thing (even if people are paying rent to sleep in stairwells), and the steady dumbing down of the populace with a steady diet of intrusive media and ubiquitous advertising is even better.

With Earth conquered, it’s time now for advertising to seek new worlds to sell, and that’s where Mitch gets the biggest break of his career – a project to sell Venus as a future home to (unsuspecting) consumers who will become future colonisers. The only hitch is that terraforming Venus to be habitable may take a while and the only man to have survived a trip to Venus is a midget astronaut, and that’s only the beginning of his role in the story. (If you’re thinking Mad Men in Space, you’d not be too far off the mark. Jon Hamm would make a great Mitch Courtenay and no points for guessing who we’d like to see as the midget astronaut).

The other hitch is the ‘Consies’ or Conservationists, an underground ‘terrorist’ movement that seeks to undo advertising’s biggest dreams. The group has its own plans for the Venus project, which is now Mitch’s baby. When not trying to convince his temporary, trial wife to make their agreement permanent, Mitch visits places to get ‘consumer insights’ from focus groups. And that’s when the trouble begins. People are out to get him, and get him they do as Mitch finds himself kidnapped, his identity as a Copysmith Star Class erased (with news of his death widely published) and sent to work on a labour farm run by his own ad agency under a new name, consigned to debt slavery and addicted to the products that he himself once sold to consumers. He’s one of them now, the have-nots, the ‘consumers’.

His job is to feed Chicken Little, a bio-engineered chicken heart that keeps growing and from which meat is sliced off and sold as real, nourishing protein to the masses. Till he bumps into the Consies or the World Conservationist Association. And so begins a clash of ideologies and inner conflict and the outcome isn’t that predictable. To start with, on reading the Consie charter, the first thing he can think is how badly it’s been written, or rather ‘copysmithed’. Once a copywriter, always a propagandist.

Mitch puts his advertising skills to good use to try and make his way back to his agency and reclaim his rightful place in the world and see the Venus project to fruition (which he does, but not in the way he’d imagined).

It’s never as simple as it sounds. There are twists and turns along the way. No one is what they seem, nothing is as it looks, and Mitch finds that out one reveal at a time. And yes, there’s also the small matter of Mitch’s temporary trial wife, who refuses to make their marriage permanent as she’s a doctor and has no time to cook and clean for him, which he expects from her. Whether the novel has a happy ending or not depends on who – and what – you’re rooting for.

It has been compared to Huxley’s Brave New World and contrasted with Orwell’s 1984.

At a time when science fiction wasn’t this big or this respectable a genre, it is to the credit of Pohl and Kornbluth that they wrote a novel that caught the attention of The New York Times enough for the publication to call The Space Merchants “a novel of the future that the present must inevitably rank as a classic.” It has been compared to Huxley’s Brave New World and contrasted with Orwell’s 1984. In it many people have found the seeds of many contemporary SF novels and ideas, which is natural given the number of SF writers who’ve been influenced by The Space Merchants. It even had a sequel, The Merchant’s War (published in 1984) but written solely by Frederick Pohl as his collaborator CM Kornbluth had tragically passed away at the age of 34, a few short years after The Space Merchants came out.

Beyond just ideas and its portrayal of a plausible future of a materialist dystopia (utopia?), the novel has quite a share of its own brave new words: from ‘soyaburger’ to ‘moon suit’, the contraction ‘R&D’, and the use of the word ‘survey’ as a verb to denote carrying out a poll (or in advertising terms, market research).

The Space Merchants would have been relevant today even in its original form, but to contemporise it a bit and update the science to be a little more accurate and up-to-date, Pohl revised – or rather made some cosmetic changes – to the novel in 2010. In the newer editions, we have terms that are more familiar and companies that are more so, including Microsoft, Walmart and yes, Bollywood.

But even without these updations, the world of The Space Merchants echoes the extremes of the world we live in, uncomfortably so. So you don’t really need to worry about the edition you lay your hands on. In fact, some of the older editions have better covers. So if you’re the type of reader who judges a book by its cover as much as what lies between them, you’re in for a win-win situation.

Go on then dear reader, pick up this classic and give it a spin. And once you do, tell us what you thought of it. I’ll see you next week on another edition of #NWWonFD. Live long and prosper!

Subscribe to FactorDaily

Our daily brief keeps thousands of readers ahead of the curve. More signals, less noise.