A few days ago, Feminism in India editor Japleen Pasricha wrote a viral post about Facebook taking down some of her photographs for allegedly violating Facebook policies and “community standards” (It’s 2016 And Facebook Is Still Terrified Of Women’s Nipples).

And now, yet another Indian visual artist’s work has been taken off Instagram and her account suspended for several hours, for sharing images that Instagram deemed to be “violating community standards.”

On Wednesday, Bengaluru-based artist and photographer Indu Antony had shared a photograph of another artist, Nidhi Mariam Cariappa’s, work. Antony, whose photos and photo essays have frequently touched upon gender, sexuality and the body, is working on a series of photographs featuring Cariappa’s work, in which she uses the female body as a “living, breathing canvas”. A few hours after posting the image — a black-and-white photograph of female breasts adorned with body paint — Antony found that she had been locked out of her own Instagram account and received a notification saying that the post had been removed.

Though her access to the account has been restored now, Antony is justifiably incensed by the diktat. “So female nipples are a problem, but male nipples are fine. What’s wrong with women’s breasts and nipples? They are just parts of the body,” says Antony.

Well, if one were to go by Facebook and Instagram’s much-discussed community standards, female breasts and nipples are inherently sexual and titillating in nature, whereas male nipples are simply body parts that do not have the potential to disturb or offend anyone — the equivalent of ears or toes.

It is pretty much impossible for the seemingly conventional and literal-minded Facebook and Instagram algorithms to accept that female bodies can be portrayed in ways that express beauty and confidence rather than be specifically arranged in a manner to satisfy the male gaze. Perhaps we can blame the porn industry that has always visualised the female body as an instrument for satisfying male desire.

Now, female photographers and artists are trying to reclaim the female body and change that perception, but they have come up against the seeming prudery of some of the biggest and most powerful digital publishing platforms in the world: Facebook and Instagram.

Pasricha, whose posts have been taken down and account suspended multiple times, calls this “nothing but a form of censorship.” “Facebook can’t seem to be able to distinguish between sexual and non-sexual imagery. In fact, I’ve been surprised to notice that they don’t actually censor breasts — if they are even marginally covered — but they seem to have a big problem with nipples,” says Pasricha. As she wrote in a widely shared post on the Feminism in India website, “time and again, Facebook proves to be that Uncle who keeps telling you your skirt is too short, but keeps a stack of highly sexualized and objectifying images of women in his folder.”

Suspended from @facebook yet again for 3 days for sharing this article. Nyaya kaha h? KAHA HAI NYAYA???///https://t.co/YdtYarqEPy

— Japleen Pasricha (@japna_p) November 7, 2016

In her post, she also points out that Facebook today is all-powerful; Espen Egil Hansen, the editor-in-chief of Aftenposten, a Norwegian daily newspaper, called Mark Zuckerberg “the most powerful editor-in-chief in the world.” “Listen, Mark, this is serious. First you create rules that don’t distinguish between child pornography and famous war photographs. Then you practice these rules without allowing space for good judgement. Finally you even censor criticism against and a discussion about the decision — and you punish the person who dares to voice criticism,” Hansen wrote in his open letter to Zuckerberg.

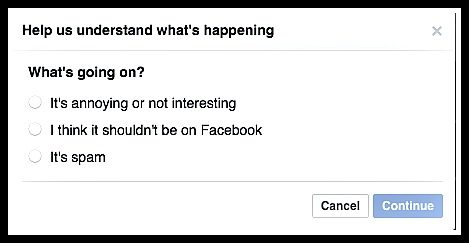

The problem is, Facebook and Instagram don’t actually employ that many editors (to be fair, given the volume of posts, that’s not a practical solution). While the ‘take-down’ process is not very transparent, most experts agree that the first complaints about a post comes from human users, who are asked to narrow down their reasons for asking a post to be taken down. When you report a post, the first step is to list your reason by choosing one of three options:

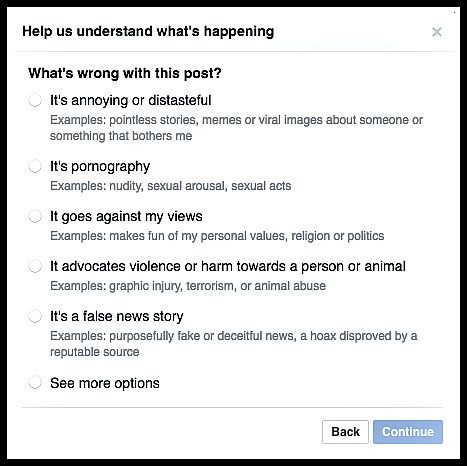

To test this, I chose ‘I Think it shouldn’t be on Facebook’ and was taken to this screen:

When I clicked on the first option, I was given the option of blocking or hiding posts from the group (essentially Facebook was telling me it was my problem). On choosing the second (“It’s pornography”) option, I got a choice to submit the page for a review by Facebook.

It’s widely assumed that this is the process by which posts that are deemed “pornographic” by a certain section of users (no matter how non-pornographic they are, for example the famous photo of the ‘Napalm girl’ from the Vietnam War, which Facebook took down leading to a worldwide hue and cry) are deleted. If a certain number of users report a post for nudity and pornography, it is taken down by Facebook’s algorithms.

A few recent incidents of unreasonable takedowns involving well-known works of art seem to have prompted Facebook to tweak its guidelines to change its nudity policy to allow “newsworthy” photographs; writers at the Think Progress blog surmised that “Facebook is essentially saying that if a work passes the SLAPS test — if it has serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value — its worth outweighs its potential ability to scandalize or offend.”

It appears as if Antony’s and Pasricha’s posts didn’t pass the test, or were not considered for it at all. Pasricha says she has met with Facebook representatives in India and discussed their policies, questioning why some posts, such as misogynist, virulently anti-women rants shared by the numerous ‘Men’s Rights Activist’ (MRA) groups on Facebook are not taken down despite being reported again and again for hate speech. “Their response was they have to allow such posts because it pertains to free speech. They told me I could block or hide messages from these groups,” says Pasricha. “So essentially, I have to look the other way when MRAs say vile things about women, but my photographs will be deleted because they show certain parts of a woman’s body in a non-sexual, artistic way.”

“Facebook is essentially saying that if a work passes the SLAPS test — if it has serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value — its worth outweighs its potential ability to scandalize or offend”

— Think Progress blog

Artists like Antony and activists like Pascricha cannot wish away the need to be on platforms like Facebook and Instagram. In the digital age, they are extremely potent ways of disseminating information and getting their work seen by others. But frequent deletions and suspensions also carry the threat of a permanent ban. “The last time my account was suspended (on November 7 for three days for sharing a story about how women are made to feel ashamed of their breasts), I got a notification saying I was facing a permanent ban and that the Feminism in India page on Facebook could be deleted for good if I violated community standards again. That means three years of work, of building a community and creating a space where we can talk about feminism in India, could potentially be lost. That is a scary thought,” says Pasricha.

Subscribe to FactorDaily

Our daily brief keeps thousands of readers ahead of the curve. More signals, less noise.

To get more stories like this on email, click here and subscribe to our daily brief.

Lead visual: Rajesh Subramanian