Isaak Judah Ozimov chose his own birthdate. He could have been born as early as October 1919, but there was no way of knowing, given the uncertainty of those times. His name changed to Isaac and — because of his father’s unfamiliarity with the English alphabet — Ozimov became Asimov when the family immigrated to the USA when he was barely three. His mother gave his birthdate as September 7, 1919 so that she could get him into school a year earlier.

When Asimov found out years later, he had it changed to the date he preferred and personally celebrated, January 2, 1920 (belated happy birthday, Dr. Isaac Asimov!).

If he hadn’t, he would’ve escaped — by virtue of being overage and ineligible – being drafted into the US Army during WW II. While his army career was brief (just nine months), he rose swiftly up the ranks to become Corporal because of his prowess in…. typing!

Typing. Asimov loved typing. And his output of hundreds of books and thousands of well-written letters are a testament to that. ‘Prolific’ is an understatement. He once said, “If the doctor told me I had six minutes to live, I’d type a little faster.” But from that typewriter emerged some of the most influential ideas, prophetic words and timeless stories ever told (or typed). His Foundation series is amongst the cornerstones of sci-fi. So is his Robot series. Many of his short stories – starting with the first one published in 1939 – regularly make it to the list of top SF short stories, even to this day. And these stories, more than being just great reads, have inspired countless people to take to the sciences, like Nobel laureate and economist Paul Krugman who took up economics after reading Foundation and AI pioneer Marvin Minsky, who was brought to his subject by Asimov’s Robot stories.

He coined brave new words like ‘robotics’, ‘roboticist’, ‘psychohistory‘ and even the term ‘social science fiction’ to describe most of his stories (the term has since been used to define the sub-genre of SF that concerns itself more with people and the evolution of human society than with spaceships, far-out technology and aliens). And he accomplished all of this with the simplest of prose, to the point of being bare and unembellished, with simple narrative structures.

With the kind of ideas he had, there was no need for flowery descriptions; just plot and functional dialogue. There was no need for spectacular flourishes; the idea itself was the spectacle! Perhaps it was this style of wanting to convey to his readers in unambiguous terms what he was talking (or typing) about that stood him in good stead when he wrote books about his first love, science – for if he liked science fiction, he like writing about science even more.

Not because he had confidence in scientists being right, but because he had so much confidence in non-scientists being wrong.

In Asimov’s opinion, wilful ignorance was a sin, and society needed to know, appreciate and understand science if we were to be truly informed and enlightened. He believed that only scientists can understand the universe. Not because he had confidence in scientists being right, but because he had so much confidence in non-scientists being wrong. “Anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that ‘my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge,’” said Asimov, reflecting that, “The saddest aspect of life is that science gathers knowledge faster than society gathers wisdom.”

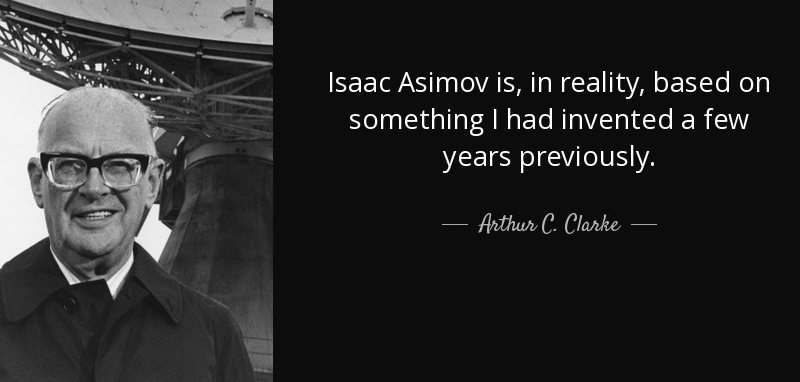

A tenured professor of biochemistry at Boston University (with a PhD in chemistry), Asimov in fact wrote an equal amount – if not more – of non-fiction popular science books and articles as he did science fiction. “The great explainer of our age,” said his fan and later friend, Carl Sagan, referring to Asimov’s prolific output and efforts in popularising and desmystifying science. Soon after Asimov’s death, Sagan wrote: “…I worry about the rest of us, with no Isaac Asimov around to inspire the young to learning and to science.” As for Asimov himself, he liked to be considered and known more as a science writer than a science fiction writer. And he was acknowledged as such by the other stalwart of his time, Arthur C. Clarke, himself an accomplished science writer and winner of the Kalinga Prize awarded by UNESCO for popularising science. Therein lies a tale.

As for Asimov himself, he liked to be considered himself and known more as a science writer than a science fiction writer.

The Golden Age of Science Fiction, as it is called, lasted a decade or so starting from the late 1930s, when modern sci-fi took shape. Straddling the landscape were the ‘Big Three’ authors – initially Isaac Asimov, Arthur C Clarke and AE Van Vogt (with Robert Heinlein soon replacing Van Vogt). It was inevitable that both Asimov and Clarke would cross paths, and they soon settled into years of amicable rivalry and the trading of witty insults. But who was the best of these two? The Clarke-Asimov Treaty of Park Avenue (or sometimes just the Park Avenue Pact) settled that question once and for all.

Clarke and Asimov once found themselves in the same taxi in New York, sharing a ride to Park Avenue. Over the course of their journey, each chose his ‘specialty’ so to speak, and thus arrived at an amicable agreement, which stipulated that when asked each would insist that the other is the world’s greatest writer in his specialty, while referring to himself as merely the second-best. Under these terms, Asimov would insist that Clarke was the world’s greatest science fiction writer, while Clarke would maintain that Asimov was the world’s best science writer.

In fact, in accordance with the pact, Arthur C. Clarke even dedicated a book of his to Asimov with the words, “In accordance with the terms of the Clarke-Asimov treaty, the second-best science writer dedicates this book to the second-best science-fiction writer.”

So if Asimov liked to write science fiction, and loved to write about science, what did he enjoy writing most? By his own admission, it would have to be the Black Widower series, over 60 short stories that – in my opinion – deserve their rightful place amongst the mystery genre’s most enjoyable and finest tales. The series revolves a club called the Black Widowers (after the spider) whose six members – a lawyer, a mathematician, a novelist, a chemist, a cryptographer and an artist – meet for dinner regularly in a private room. Each member, in turn, brings an interesting guest along. Post-dinner, the guest is asked about himself and as it follows, the guests have troubles and issues – some of them real crimes – that the Black Widowers then try to solve by bringing their eclectic knowledge to the mix, with the key insight and oftentimes answer provided by their waiter Henry Jackson (modelled on Jeeves; Asimov’s way of paying tribute to one of his favourite authors, PG Wodehouse).

The Black Widower series — over 60 short stories that in my opinion deserve their rightful place amongst the mystery genre’s most enjoyable and finest tales

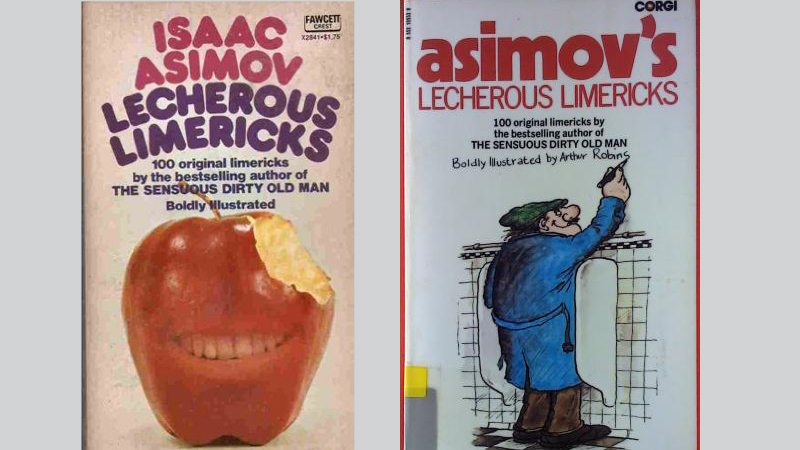

Science fiction, science, technology and mystery apart, Asimov also wrote over a dozen books on history, a guide to Shakespeare, annotations to Milton’s Paradise Lost, the Lucky Starr series of scifi adventure stories for children under the pseudonym ‘Paul French’, a three-volume autobiography, an over-1000-pages guide to the Bible, lots and lots of essays, limericks for children and oh yes, bawdy, obscene poetry and lecherous limericks (five volumes of them). Look them up!

Just as calling Asimov ‘prolific’ would be an understatement, it would also be futile to overstate his intellect, his vast range of interests and activities and his abundance of talent. Speaking about himself and his talent, in this case about writing rude verse, but surely applicable to all else, Asimov starts by planting the question himself by saying, “The question I am most frequently asked is, ‘How do you manage to make up your deliciously crafted limericks?’” To which he readily gives the answer: “It’s difficult to find an answer that doesn’t sound immodest since ‘Sheer genius!’ happens to be the truth. It is terrible to have to choose between virtues of honesty and modesty.”

Well, so was Asimov immodest and arrogant? People who knew him say otherwise; after all, Asimov let his Mensa membership lapse because he found that many members of this high-IQ society were arrogant about their supposed intelligence. He was an atheist, and a Humanist, serving as the president of the American Humanist Association until his death in 1992 (his successor as President of the AHA was his friend, the writer Kurt Vonnegut Jr.). And also, Asimov was humble enough to admit once that there were two people whose intellects surpassed his own – Carl Sagan and Marvin Minsky.

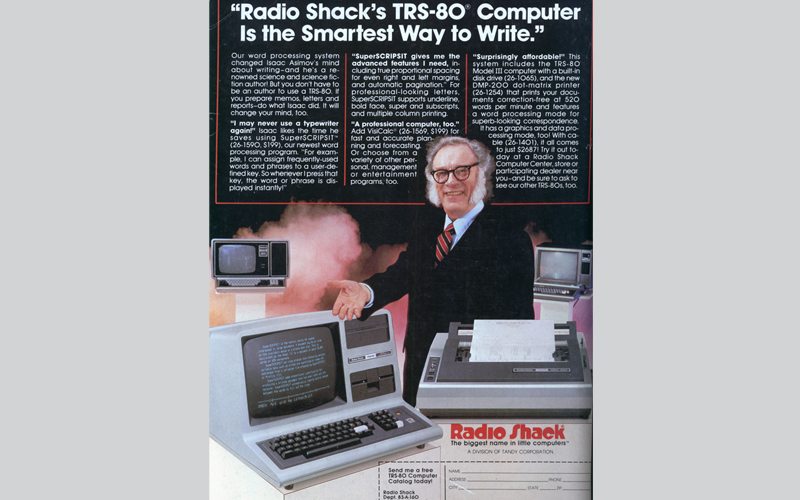

And between all of this – writing, giving speeches, and being member of various associations and clubs like Baker Street Irregulars and The Wodehouse Society, he also found time to be the face of Radio Shack, plugging all their many cutting-edge, technologically-advanced products, while rocking those sideburns.

But to get a taste of Asimov is to read his brilliant fiction. In case you are wondering where to begin – or as happens with fans and their much-loved authors, what to re-read? – here below is a handy list of Asimov essentials. My subjective preferences have been balanced off by Asimov’s own favourites, and other such reasons:

Foundation series: The original and core trilogy consisting of Foundation, Foundation and Empire, and Second Foundation. Only winner, thus far, of a Hugo Award for best all-time series. The trilogy that spurred Paul Krugman to take up economics, and one he recommends highly. Ditto for Elon Musk, who counts this among the books that inspired him.

The Complete Robot: A collection of all of his classic Robot short stories, in which Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics first appeared. This has influenced most stories with robots ever since, as well as people working in the field (a case could be made for calling them the Asimov-Campbell Laws, because Asimov explicitly stated that the Three Laws were originated by John W. Campbell, the editor who ‘discovered’ Asimov and as editor of the magazine Astounding Science Fiction, generally considered with shaping sci-fi’s golden age).

The Gods Themselves: Asimov’s favourite novel, which went on to win both the Hugo and Nebula awards. Particularly satisfying for Asimov personally because of a) the middle section, which he thought was the biggest, and most “over-my-head writing” (his words) he ever produced and b) it had non-human aliens and sex, things which Asimov was considered incapable of writing about or, at the very least, accused of running away from.

The Best Science Fiction of Isaac Asimov: A collection of 28 short stories, each introduced by the author himself explaining his reasoning behind the story. It contains two of his favourite sci-fi stories: The Last Question (considered one of the greatest sci-fi stories of all time) and The Ugly Little Boy.

Nightfall: Again, one of the most acclaimed short stories in sci-fi, and later expanded into a novel with Robert Silverberg, himself an accomplished science fiction writer.

The Best Mysteries of Isaac Asimov: A collection that introduces us to the Black Widowers series with 15 stories, 9 tales taken from Asimov’s other series, Union Club Mysteries, and other standalone mystery stories including two featuring his young detective Larry, high school student.

There’s more, lots more, but this short list would give a reader an idea of Asimov’s fiction and why he is rated so highly (to put it mildly). And to make it easier to start off with this list, the #NWWonFD contest is back! Yes, we are going to give away a copy of the Foundation Trilogy. A hardcover edition – cloth bound – from the Everyman’s Library imprint, no less, and which contains all three novels of the core trilogy. Yes, you could call it a collector’s edition if you will. And it does look really great on a bookshelf.

And all you have to do is tell us, ‘What would you tell Isaac Asimov – if you somehow got unstuck in time – and had 15 seconds with him?’ That’s it. Tweet us your answers with the hashtag #NWWonFD, or leave a comment on the FactorDaily Facebook page, or write your answer as a comment to this piece, before Thursday, January 12, 2017 comes to an end (IST; standard, not stretchable).

On that note, I wish you all the best should you decide to participate! And as always, wish you all to Live Long and Prosper! I hope to see you again next Friday, for another edition of New Worlds Weekly, only on FactorDaily.

Subscribe to FactorDaily

Our daily brief keeps thousands of readers ahead of the curve. More signals, less noise.

To get more stories like this on email, click here and subscribe to our daily brief.

Disclosure: FactorDaily is owned by SourceCode Media, which counts Accel Partners, Blume Ventures and Vijay Shekhar Sharma among its investors. Accel Partners is an early investor in Flipkart. Vijay Shekhar Sharma is the founder of Paytm. None of FactorDaily’s investors have any influence on its reporting about India’s technology and startup ecosystem.