“You’re the ones who’ve been slacking off!” proclaimed Michael Crow, President of Arizona State University to Neal Stephenson at a Future Tense conference after Stephenson had – speaking at the conference – lamented the decline of the manned space programme and of our current inability as a society to execute on the Big Stuff. Crow was of course referring to the authors of science fiction – the genre that had sparked many a young mind to take up science, lit up the imagination of many an inventor, but has in recent years tended to veer more towards dystopian and pessimistic futures instead of a more hopeful one, a dark and cynical rut that Stephenson himself readily admits he may have fallen into but one that he doesn’t regret.

From the time of Jules Verne’s submarines to Star Trek’s communicators inspiring Martin Cooper to develop cellphone technology up to Stephenson’s own Snowcrash being a major influence on the development of Google Earth, science fiction has always showed us what we as a people are capable of when we decide to Get Big Stuff Done (GBSD). MRI machines, geostationary satellites, flat screen TVs, credit cards – the list can go on and on – all of these first took shape between the covers of a science fiction novel. As Stephenson notes, ‘There’s definitely some kind of a feedback loop between science fiction and technological fact’.

Processing power that is magnitudes of order more than what put man on the moon is used to throw birds at pigs, crush candy and apply filters to photos no one wants to really see.

But that’s just the starting point. SF at its most inspirational is never about technology itself in isolation or just about machines but about humanity’s relationship with them. In the words of sci-fi author Gareth Powell, “In this respect, science fiction is useful as a tool, not for predicting the future, but for instead modelling a vast range of possible futures. As our society develops and changes, science fiction is there to show us what will happen if we continue along our current path”.

Neal Stephenson’s experience at the Future Tense conference led him to think along the lines of what science fiction can do to spur society at large and engineers and scientists in particular to once think big once again, as in the 20th century, and how to GBSD. Because innovation nowadays isn’t. There aren’t big risks taken, instead incremental improvements on existing systems and improvisations on existing tech is celebrated. There is no ‘long run’ when your vision doesn’t extend beyond the next quarterly report. Processing power that is magnitudes of order more than what put man on the moon is used to throw birds at pigs, crush candy and apply filters to photos no one wants to really see.

Outlining his thoughts in a World Policy Institute (WPI) article titled Innovation Starvation, Stephenson notes how people at the conference were more confident than me that SF had relevance — even utility — in addressing the problem of innovation starvation, and put forward theories he’d heard as to why:

1. The Inspiration Theory. SF inspires people to choose science and engineering as careers. This much is undoubtedly true, and somewhat obvious.

2. The Hieroglyph Theory. Good SF supplies a plausible, fully thought-out picture of an alternate reality in which some sort of compelling innovation has taken place. A good SF universe has a coherence and internal logic that makes sense to scientists and engineers. Examples include Isaac Asimov’s robots, Robert Heinlein’s rocket ships, and William Gibson’s cyberspace. As Jim Karkanias of Microsoft Research puts it, such icons serve as hieroglyphs — simple, recognizable symbols on whose significance everyone agrees.

The thinking behind this lead directly to Neal Stephenson founding Project Hieroglyph, a project of science fiction writers, scientists and engineers to depict future worlds in which BSGD. Never underestimate the constructive influence of science fiction. As he notes in the WPI article, it was time for SF writers to start pulling their weight and supplying big visions that make sense. Hence the Hieroglyph project.

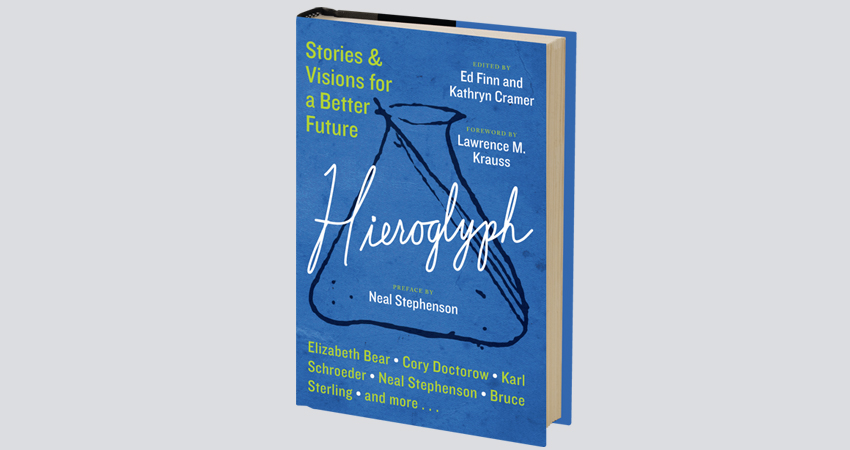

Hieroglyph is today a project of the Arizona State University’s Center for Science and the Imagination, who Neal Stephenson partnered with, and the first anthology of science fiction short stories emerged from this project in 2014 aptly titled, Hieroglyph: Stories and Visions for a Better Future. Edited by science fiction writer, editor, co-founder of The New York Review of Science Fiction and a World Fantasy Award winner Kathryn Kramer; and Ed Finn, founding director of the Center for Science and the Imagination at ASU, Hieroglyph is, to quote Stephenson from the WPI article, “…an effort to produce an anthology of new SF that will be in some ways a conscious throwback to the practical techno-optimism of the Golden Age .”

Hieroglyph features a veritable who’s-who of contemporary science fiction. Karl Schroeder, known for deeply philosophical streak, his far-future speculations on nanotech, terraforming, augmented reality and the man who originated the concept of thalience; two-time Hugo Award winner Bruce Sterling, whose novels helped define the genre of cyberpunk; Cory Doctorow, who is also the co-editor of Boing Boing; the ever-awesome Madeline Ashby; multiple Hugo Award Winner Elizabeth Bear; Indian speculative fiction writer Vandana Singh; David Brin; Rudy Rucker, the mathematician, computer scientist and writer; Paul Davies, the English physicist; Gregory Benford, astrophysicist and sci-fi author. And of course, Neal Stephenson. These are just some of the writers and scientists (in some cases, both) who have contributed to this anthology filled with ‘stories to make you think big’. Stories in which science and technology have improved the world, instead of destroying it (there are no evil robots anywhere!).

This lead to Neal Stephenson founding Project Hieroglyph, a project of science fiction writers, scientists and engineers to depict future worlds in which Big Stuff Gets Done

Each of the sci-fi stories in Hieroglyph is grounded in real science, populated by real people in relatable cultures, written with scientific and engineering inputs and portray one big idea and/or a plausible future that may sound or look audacious at first but most of which are realistic in the near-term; the thinking being that a young engineer or maker interested in them should be able to make substantial progress on it during his or her lifetime.

Neal Stephenson’s story Atmosphæra Incognita kicks-off the anthology, in which an ambitious tech entrepreneur constructs a 20-km tall tower that jump-starts the defunct steel industry, reveals novel methods for generating renewable energy, encounters the most exotic wind and weather phenomena the Earth has to offer and houses the First Bar in Space. I’ll drink to that! Closing the anthology, meanwhile, is Bruce Sterling with his story Tall Tower which is about the same tower, albeit 200 years in the future.

Cory Doctorow – whose story The Man Who Sold the Moon is about a scrappy group of makerspace hardware hackers and Burning Man devotees who send autonomous 3D printing robots to the Moon to print building materials for future generations of spacefarers, overcoming the challenges of crowdfunding a Moon mission and perfecting an open-source engineering marvel – wrote that stories in Hieroglyph are not “optimistic or pessimistic about the future. Instead, they are hopeful about it.” Doctorow’s story for Hieroglyph, by the way, won 2015 Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award.

Vandana Singh’s gem, Entanglement, is about how technology can increase empathy and connectedness

Karl Schroeder’s Degrees of Freedom uses augmented reality to provide a fascinating and inspiring lens on democracy, legitimacy, and collective decision making. Kathleen Ann Goonan’s evocative and almost lyrical story Girl in Wave: Wave in Girl looks at how education itself can and should be reimagined and refined and how improving the manner in which we teach could lead to a better future. Vandana Singh’s gem, Entanglement, is about how technology can increase empathy and connectedness, and posits an experimental network called Million Eyes through which people confronting climate change – from biogeochemists to children in rural India – support one another.

Outraged by the rise of the Mediasphere, a heavily surveilled and sanitized network controlled by the government and corporate interests, dronepunks seed the skies with flying routers, creating the Drone Commons, an unregulated mesh network propagated by masses of outsiders, rebels and the unrepentantly strange, in Lee Konstantinou’s story, Johnny Appledrone vs. the FAA. And speaking of drones, the essence of Brenda Cooper’s Elephant Angels, in which animal activists use drones to track poachers, has already come true, right here in India.

Of course, no one, not least the authors of these short stories, is under a Pollyanna-ish impression that these sci-fi stories by themselves will make the world a happy place, but Stephenson and many at Hieroglyph hope that they will at least have a constructive influence. So if you are amongst those who believe in a better future through science and technology, enjoy a good story, and are kicked about new ideas and hopeful tomorrows, pick up a copy of Hieroglyph, enjoy the read and join in the conversation over at hieroglyph.asu.edu

Of course, no one is under a Pollyanna-ish impression that these sci-fi stories by themselves will make the world a happy place

Let me end this edition of New World Weekly with an extract from Bruce Sterling’s Tall Tower, which encapsulates the spirit of why we should innovate, invent more and GBSD. “Mankind can build a Great Thing. Sometimes we do it. But then we have to live with the consequences of greatness. What does a Great Thing tell us about ourselves? Not that we are great, but that our Great Things are so rare, and so much abused. So many in our dreams, so few to loom like towers in the light of day.”

That’s it until the next week. Do share your opinions on Hieroglyph and thoughts about the role of sci-fi, and any suggestions or feedback you have for New Worlds Weekly. Leave a comment below or tweet to us with the hashtag #NWWonFD. And long may the Force be with You!

Subscribe to FactorDaily

Our daily brief keeps thousands of readers ahead of the curve. More signals, less noise.

To get more stories like this on email, click here and subscribe to our daily brief.

Lead image: An illustration from the book by Haylee Bollinger for James Cambias' story, Periapsis, which portrays life on Deimos, the near-zero-gravity moon of Mars and asks 'what will teen love be with hormone regulators and augmented reality implants?'