Literature, like all art, is open to interpretation. And the creator’s own interpretation is just one of them, which leads us to the question: to what extent is it the definitive interpretation?

There’s an old joke that highlights the difference between authorial intent and its subsequent interpretation. It goes like this:

Imagine a sentence, ‘The curtains were blue.’

What the teacher/critic thinks: ‘The curtains represent his immense depression and his lack of will to carry on.’

What the author meant: ‘The curtains were freaking blue!’

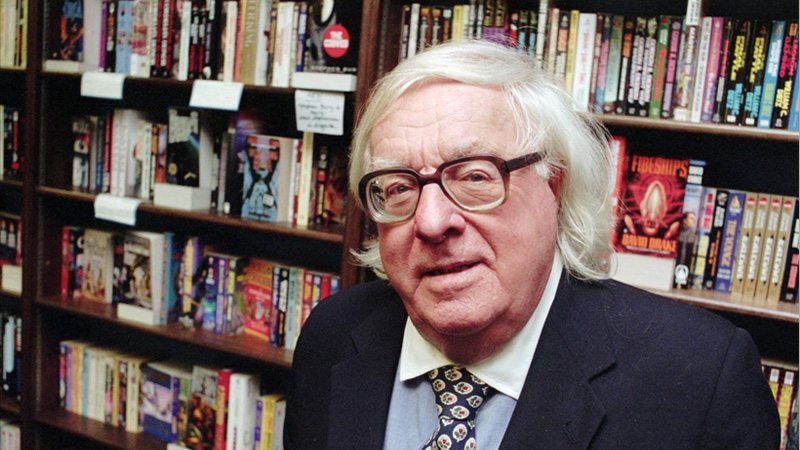

Something similar played out in real life more than a decade ago at the California State University at Fullerton where the author Ray Bradbury was speaking about his most famous book, Fahrenheit 451. The students at the talk insisted that the novel was about government censorship. Bradbury disagreed. The students refused to listen to the explanation of what he – the author himself – thought the book was really about. After all, don’t all the countless reviews and essays say that’s what the book is about? Government censorship and book burning? After half an hour of arguing with them and telling them that they were wrong, he said, “F*** you” (a word he says he’d never used before this incident) and then in true Bradbury fashion, stormed out of the classroom.

So, if the main theme is not censorship, what is Fahrenheit 451 about? After all, it is for a reason that the error status code displayed when a user requests a page that cannot be served for legal reasons (such as a web page censored by a government) is HTTP 451: Unavailable For Legal Reasons.

Here’s the long answer.

A short note before we proceed. What follows below may contain some very minor spoilers; thematically speaking, not plot-wise. But given that Fahrenheit 451 is among those science fiction books to have made it out of the SF ghetto into ‘mainstream literature’, I would assume many of you have read it. If you haven’t, please do so soon, and you’ll see how relevant it is to today’s times. And worry not about proceeding further, I’ve self-censored out all the plot and story spoilers and eliminated all specific mentions of any character or incident.

According to Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451 is not about censorship but about technology — more specifically, about the role of mindless television on society; the new opiate of the masses. Through the book, Bradbury wanted to show people that mindless, endless television was (is?) not a substitute for literature and reading. Apart from the wall-mounted television sets (which he predicted in the book in 1953), he also predicted that other constant purveyor of entertainment and communication: the in-ear headphones (Air Pods anyone?) that he called ‘thimbles’, which also helped keep the populace too busy to think.

But what about the book burnings? Aren’t books outlawed in the world of Fahrenheit 451? Well, there was no reason for books to exist anymore because people stopped reading. To quote from the book, where a character speaks about how things came to be so (and I quote from my prized author-signed copy of the Del Rey 50th Anniversary edition of Fahrenheit 451), “Picture it. Nineteenth-century man with his horses, dogs, carts, slow motion. Then, in the Twentieth Century, speed up your camera. Books cut shorter. Condensations. Digests. Tabloids. Everything boils down to the gag, the snap ending. Classics cut to fit fifteen-minute radio shows, then cut again to fill a two-minute book column, winding up at last as a ten- or twelve-line dictionary resume. I exaggerate, of course. The dictionaries were for reference. But many were those whose sole knowledge of Hamlet… was a one-page digest in a book that claimed: ‘now at least you can read all the classics; keep up with your neighbours.’ Do you see? Out of the nursery into the college and back to the nursery; there’s your intellectual pattern for the past five centuries or more.”

In the world of Fahrenheit 451, intellectualism and independent thinking had become abhorrent, making anti-intellectualism another theme of the book. From the book: “With school turning out more runners, jumpers, racers, tinkerers, grabbers, snatchers, fliers, and swimmers instead of examiners, critics, knowers, and imaginative creators, the word ‘intellectual,’ of course, became the swear word it deserved to be.”

Fahrenheit 451 posited a culture so diverse that every group – defined by colour, race, profession, hobbies – was a minority. And a time came when nothing could be written without offending someone or the other; without some group or the other outraging.

So where did it start? And where does the government fit in? It started with people, the chief culprits — not the government, which is at best a very willing ally to the whims of the populace to serve its own ends. Fahrenheit 451 posited a population so big, a culture so diverse, that every group – defined by colour, race, profession, hobbies and what not – was a minority. And a time came when nothing could be written without offending someone or the other; without some group or the other outraging. As the book puts it, “Don’t step on the toes of the dog lovers, the cat lovers, doctors, lawyers, merchants, chiefs, Mormons, Baptists, Unitarians, second-generation Chinese, Swedes, Italians, Germans, Texans, Brooklynites, Irishmen, people from Oregon or Mexico. The people in this book, this play, this TV serial are not meant to represent any actual painters, cartographers, mechanics anywhere. The bigger your market… the less you handle controversy, remember that!”

Bradbury didn’t just foresee political correctness, he took it to an extreme, where it had crossed over into absurdity. He saw the perils of “playing it safe.”

The government in Fahrenheit 451 is not in the mould of the Big Brother of Orwell’s 1984, but more a cooperative little sister, giving you what everyone wants at the cost of your critical thought. It’s like being given a choice between murder and suicide. The end is the same, but the means are different, and the means of Fahrenheit 451’s government are more insidious, because it’s self-invited by people happy with their entertainment programmes, summarized summaries and factoids. Crammed with non-combustible data and stuffed so full of useless ‘facts’ that they feel ‘brilliant’ with information, happy in their wilful ignorance. He also spoke of the extent to which technology can be used for social control and the dumbing down of a willing population. All of which bear out Bradbury’s interpretation of his own book.

Bradbury didn’t just foresee political correctness, he took it to an extreme, where it had crossed over into absurdity. He saw the perils of “playing it safe.”

And the firemen? Well, they had to do something after technological advancements had made all homes fire-proof, thus rendering them redundant. Once things got going with condensing books, removing all and any offensive bits, and taking out anything that could cause outrage to any group, all that was left were the harmless please-all footnotes – there was nothing much left to read anyway. And only after people stopped reading did the government employ the almost-unemployed firemen to burn books, which people themselves reported in (because, ‘A book is a loaded gun in the house next door!’).

On a side note, here’s a glimmer of hope for people worrying about the future of jobs, and technology making them redundant. If the firemen of Fahrenheit 451 are anything to go by, the professions per se won’t go away, but what they do will be, shall we say, ‘repurposed?’

Speaking about the book, Bradbury once said, “I was not predicting the future, I was trying to prevent it.” Seen in that light, Fahrenheit 451 becomes a cautionary tale that we could learn a lesson or three from, or at the very least stop looking at it as just a book about censorship – which implies government control – and instead look at its warning about a society that’s been doped up so high on technology and so distracted by television that they’ve lost track of reality and independent thought, and turned away from reading books (because they are outraged and offended by everything) and the habits of thought and reflection.

To quote Bradbury once again, “There are worse crimes than burning books. One of them is not reading them.”

And before we blame the government – of Fahrenheit 451 – it would serve us well to remember that only after people had voluntarily and happily given up reading, seduced by the comforts of technology, inoffensive television and mass media, did the government step in (to help of course).

To quote Bradbury once again, “There are worse crimes than burning books. One of them is not reading them.” And this sentiment is borne out in the afterword to Fahrenheit 451, where he revisits his characters and speaks to them again, and one of the chief protagonists says, “It’s not owning books that’s a crime, it’s reading them!”

So dear reader, don’t stop reading. Watch television if you will, but let it not turn you away from reading good books (also, books are almost always better than their TV or movie adaptations). They may not be able to easily set fire to Kindle Fires, but would they need to if there’s no one to read what’s stored in them? Perhaps even follow in the footsteps of Marx (Groucho, not Karl) who found television very educational, because when someone turned on the set, he would go to the other room and read. The choice, of course, is all yours. As it should be.

And speaking of choices, choosing the winner of the NWW Contest – to see who gets a copy of Ted Chiang’s must-read collection, Stories of your Life and Others – was a snap. There was only one entry, and a nice one at that from Venkatasubranaian Chandrasekran. Congratulations Venkat! I can’t think of a nicer collection of thought-provoking modern science fiction stories that could tempt someone away from television. Do send us your mailing address and we’ll make sure you get your copy before Arrival arrives, so you can read the story before watching the movie, if you wish.

On that note, I sign off for this week. Do share your thoughts, comments and opinions about Fahrenheit 451 – and whether you agree, disagree with Ray Bradbury – or about New Worlds Weekly in general, in the comments section below or tweet to us with the hashtag #NWWonFD. Live long and prosper!

Subscribe to FactorDaily

Our daily brief keeps thousands of readers ahead of the curve. More signals, less noise.

To get more stories like this on email, click here and subscribe to our daily brief.

Disclosure: FactorDaily is owned by SourceCode Media, which counts Accel Partners, Blume Ventures and Vijay Shekhar Sharma among its investors. Accel Partners is an early investor in Flipkart. Vijay Shekhar Sharma is the founder of Paytm. None of FactorDaily’s investors have any influence on its reporting about India’s technology and startup ecosystem.